The Rio Grande Valley Refuses to Lose

The We Refuse to Lose series explores what cradle-to-career initiatives across the country are doing to improve outcomes for students of color and those experiencing poverty. The series profiles five communities— Buffalo, Chattanooga, Dallas, the Rio Grande Valley and Tacoma—that are working to close racial gaps for students journeying from early education to careers. A majority of these students come from populations that have been historically oppressed and marginalized through poorly resourced schools, employment, housing and loan discrimination, police violence, a disproportionate criminal justice system and harsh immigration policies.

Since early 2019, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has supported these five community partnerships and convened their leaders as a learning community. It commissioned Education First to write this series to share how these communities refuse to lose their children and youth to the effects of systemic racism and a new and formidable foe—COVID-19.

Chapter 1

As a 10-year-old in the 1960s, Juanita Valdez- Cox joined her parents, brothers and sisters in the field

harvesting citrus, bell peppers, broccoli and cauliflower in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, sugar beets in Colorado and onions in Michigan. During her family’s annual trek to Ohio for work, she picked tomatoes by day and cleaned and peeled them for the Campbell Soup Company by night, squeezing in school as a migrant student where she could. To help support her family full-time, she dropped out in the 10th grade and didn’t return to school until she married, more than a decade later.

As a girl, home base for her was Donna, Texas, in the Rio Grande Valley, where her family lived in a small rented house in a colonia, one of among hundreds of small, unincorporated communities along the Texas-Mexico border that to this day remain under resourced and without the quality homes, roads and other infrastructure most municipalities enjoy. “When I was growing up, we didn’t have potable water. I often asked my parents why they and all their children worked so hard but remained so poor.”

Valdez-Cox’s parents, she says, “knew the dignity of work that was feeding the nation and that they had to demand respect.” They joined the United Farm Workers (UFW), founded by César Chávez and Dolores Huerta. With fellow union members, they fought for fair wages and humane working conditions that neither federal and state governments required nor farm owners provided. They fought for drinking water in the fields. They fought for handwashing facilities to rinse away life-threatening pesticides. They fought for toilets.

They eventually won these basic human working conditions in the 1980s—along with unemployment benefits and worker’s compensation—after a series of lawsuits and organized protests. Today, Valdez- Cox is the executive director of La Unión del Pueblo Entero (LUPE), an immigrant rights organization also founded by Chávez and Huerta and a key partner of RGV FOCUS, the Rio Grande Valley’s cradle-to-career education partnership of nonprofits, business, industry and higher education.

Enséñame el sufrimiento de los

más desafortunados;

Así conoceré el dolor de mi pueblo.

Libérame a orar por los demás;

Porque estás presente en cada persona.

Ayúdame a tomar responsabilidad de mi propia vida;

Sólo así, seré libre al fin.

Concédeme valentía para servir al prójimo;

Porque en la entrega hay vida verdadera.

Concédeme honradez y paciencia;

Para que yo pueda trabajar junto con otros trabajadores.

Alúmbranos con el canto y la celebración;

Para que levanten el Espíritu entre nosotros.

Que el Espíritu florezca y crezca;

Para que no nos cansemos en la lucha.

Nos acordamos de los que han caído por la justicia;

Porque a nosotros han entregado sus vidas.

Ayúdanos a amar aún a los que nos odian;

Así podremos cambiar el mundo.

—César Chávez, Fundador de la United Farmworkers Union

Show me the suffering of the most miserable;

So I will know my people’s plight.

Free me to pray for others;

For you are present in every person.

Help me take responsibility for my own life;

So that I can be free at last.

Grant me courage to serve others;

For in service there is true life.

Give me honesty and patience;

So that I can work with other workers.

Bring forth song and celebration;

So that the Spirit will be alive among us.

Let the Spirit flourish and grow;

So that we will never tire of the struggle.

Let us remember those who have died for justice;

For they have given us life.

Help us love even those who hate us;

So we can change the world.

—César Chávez, Fundador de la United Farmworkers Union

Valdez-Cox says that faith was a defining feature of her family’s ability to endure work in the fields and continue to provide for the family. And, she says, faith animates the work of LUPE. LUPE members and staff members begin every gathering with Oración del Campesino en la Lucha, the Prayer for the Farmworkers Struggle. “It gives us a lot of encouragement to continue our work for justice,” she says. “We always ask for help to love those who hate us so we can change the world,” she adds, reflecting on late 2013 when LUPE organized fasts and prayers to respond to the armed white militia members who came to the Valley to patrol the border. She believes absolutely in the utility of those fasts and prayers. The paramilitary group’s month-long presence in the Valley, she says, passed without any incidence of violence.

“Faith informs our work here. It’s in everything.”

Chapter 2

“The people of the Rio Grande Valley bring their authentic selves to work,” says Luzelma Canales, the founding executive director of RGV FOCUS.

“Their faith is obvious in their actions and the hope and positive view of the world they bring to their work. Despite the poverty here and how hard things can be, we view the world through a love of life, through a prism of colors. That spirit of joy and love is why we sing De Colores.”

Founded in 2012, RGV FOCUS is the Rio Grande Valley’s collective impact initiative serving four counties in South Texas: Cameron, Hidalgo, Starr and Willacy. School districts, higher education, nonprofit organization and professional and community leaders work together to transform college readiness, access and success across the region in pursuit of four primary goals: (1) graduating all high school students college ready, (2) transitioning them to higher education within a year, (3) ensuring they achieve a degree or credential on time, and (4) ensuring they are employed after graduation within six months.

There are indeed many bright colors in the Valley, which is a place like few others in the United States— four counties, 37 school districts and nearly 5,000 square miles, the home to 1.3 million people, 91 percent of whom are Latino, 86 percent economically disadvantaged, and 33 percent below the poverty line. Though many consider the Rio Grande Valley to be a United States treasure, some describe it as being “in” the United States but not being “of” the United States, citing a second checkpoint 100 miles from the Texas- Mexico border residents must pass through before entering into the rest of the country. It’s both a physical and psychological barrier many residents have never crossed and those working in the country without documentation don’t dare traverse.

De Colores

De Colores se visten los campos en la primavera

De Colores

De Colores son los pajarillos que vienen de afuera

De Colores

De Colores es el arco iris que vemos lucir

Y por eso los grandes amores

De muchos colores

Me gustan a mí

Y por eso los grandes amores

De muchos colores

Me gustan a mí

—Canción folclórica tradicional

In colors

In colors, the fields dress themselves in spring

In colors

In colors, the little birds come from afar

In colors

In colors is the arch of the rainbow we see shining

And that’s why my great love is of the many

bright colors

And that’s why my great love is of the many

bright colors

—Traditional Folk Song, sung in churches and at rallies in the Valley

Patty McHatton, a former executive vice president at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley (UTRGV), recalls her first experience with the secondary checkpoint. A Florida transplant preparing for her first drive from Brownsville to Austin, the state capital, she remembers laughing when someone told her she should take her passport. “But I wasn’t laughing later,” she says. “On the drive, I arrived at what looked like a weigh station and there stood armed border patrol agents asking me to prove my citizenship. I was over 100 miles into the United States, and it was disorienting and uncomfortable. It makes you feel like you don’t belong. There’s something scary about being stopped and asked about whether you’re a United States citizen by someone who is armed while being in the United States.”

Being suspect is a regular part of life for people in the Valley, where nine out of 10 people are Latino. In the first decades of the 20th Century, Latino residents endured hundreds of recorded lynchings, some perpetrated by Texas Rangers, “Juan Crow” laws that were synonymous with Jim Crow laws in the South, segregated schools, and efforts to exterminate the Spanish language.

It’s no accident that many of the Latino-focused civil rights groups, such as the Mexican American Legal Defense Fund (MALDEF), have their origins in the state, where the expansion of the federal Voting Rights Act in 1975 was in part an effort to protect the voting rights of Latinos. It’s also where federal courts recently ruled that a 2013 voter identification law was discriminatory and where the state board of education added Mexican-American studies as an elective course only in 2014.1

Residents of the Valley know what they’re up against as they fight for justice but prefer to focus on what Valdez-Cox says are the region’s greatest assets: hope and hard work. Julieta Garcia, who led the University of Texas at Brownsville (UTB) as the first Latina in the history of the United States to head up a four-year higher education institution, uses a term she says she learned from scientists on the university’s staff to describe the region: an interface zone. “As in biology, where one ecosystem meets another and plants and animals evolve to survive and thrive in this ‘meeting place,’ we’re in a place where two cultures, languages, monetary and measurement systems come together,” she says. “It’s not a clash of zones and people or plants or animals. It’s a morphing of them. We’re hybrids here. That’s our paradigm. We see ourselves as the place where the north and south hemispheres convene. We’re not ‘less than.’ We are ‘more than.’ Our brains are enhanced by these complexities. Hope here is boundless.”

Despite the boundless hope, residents are steely-eyed about their reality: They have had to fight against racist systems through courts and through what they see as the transformative power of education.

Chapter 3

It took a lawsuit to remedy longstanding discrimination in higher education for Latinos in South Texas.

More than a century after the Texas State Constitution called for the creation of a “university of first class” in 1876, Latinos did not enjoy equal access to higher education in the state.

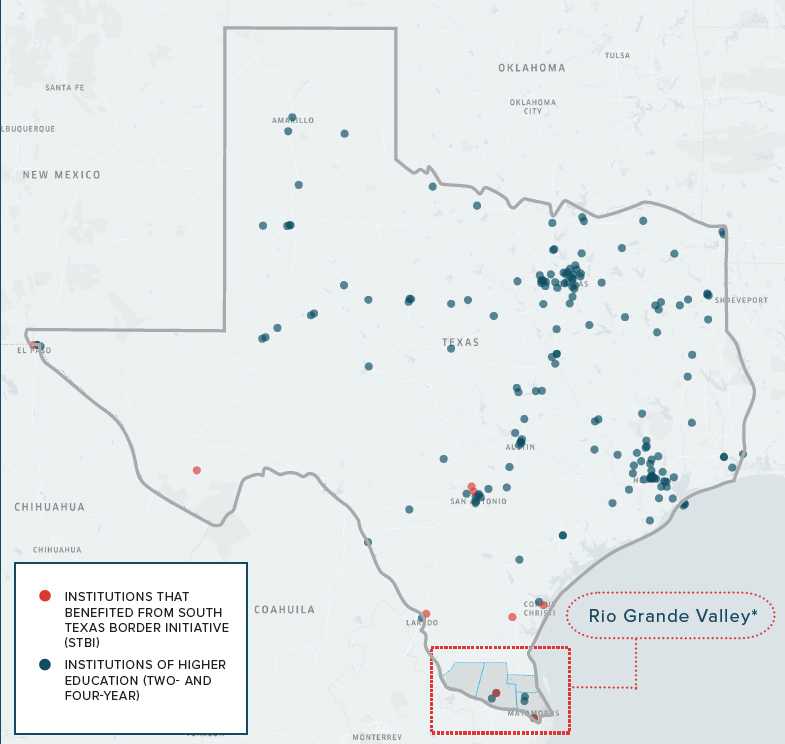

INSTITUTIONS ESTABLISHED OR IMPACTED BY THE SOUTH TEXAS BORDER INITIATIVE (1991 AND LATER)

Sources: TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD; NORTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY

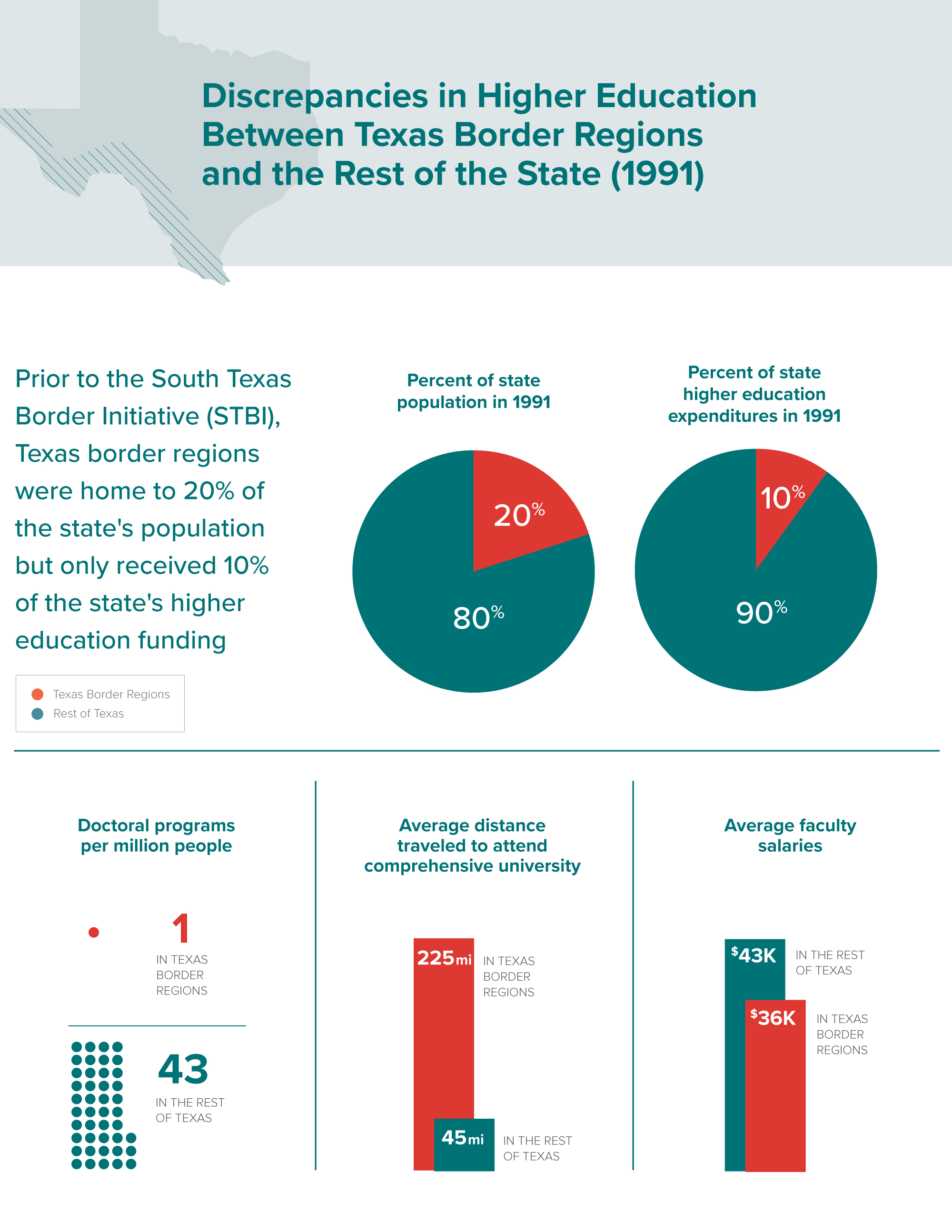

In 1930, of the nearly 40,000 students enrolled in colleges and universities statewide, less than half a percent were Mexican-American.2 In 1946, Mexican- Americans made up under 2 percent of the state’s college population, despite the fact they accounted for 17 percent of it. By 1991, these numbers had improved after the state opened institutions of higher education in South Texas, including Pan-American College in Edinburg and a branch campus of UTB. Still, huge discrepancies remained (see Table 1).

DISCREPANCIES IN HIGHER EDUCATION BETWEEN TEXAS BORDER REGIONS AND THE REST OF THE STATE (1991)

Julieta Garcia, the former president of UTB, notes that residents of the Valley are hesitant to use the word “racism” to label the root cause of these discrepancies. “Nonetheless, it is racism,” she says. Katherine Diaz, a deputy director of RGV FOCUS says, “There was a longstanding belief summed up by a question those in power have consistently asked in Texas, ‘Why do people picking fruit and vegetables in the field need higher education?’ ”

A 1987 lawsuit filed by MALDEF proved a turning point. The class-action suit accused Texas of discrimination, and in 1991, a jury ruled that the state legislature had failed to establish a “first-class” system of colleges and universities in South Texas. A court order requiring the legislature to remedy this injustice led to the creation of the South Texas Border Initiative (STBI). The legislation appropriated nearly $2 billion—$400 million to be spent in rapid response over a period of two to four years with the remainder earmarked for long-term development plans for universities in the region.

I remember going to the state capitol in Austin to request that my institution [UT at Brownsville] be allowed to add physics and music degrees. At the time we had only a single part-time professor who taught both physics and chemistry. People at the capitol laughed at me. ‘We don’t need your students to grow up and do physics,’ they said. Now the Rio Grande Valley has SpaceX. I believe one of the reasons we do is because as it was deciding where to locate, they met with students in the labs at UT-Brownsville [before it closed to usher in UTRGV]. The physics and chemistry department had grown to over 15 professors. For three hours we had super-nerds from SpaceX talking to super-nerds from the university. I believe we were key in getting SpaceX to come to the Valley.

In 1993, the state established a new community college, South Texas College, which today operates five campuses and two higher education centers in the Valley’s Hidalgo and Starr counties. Other institutions include Texas Southmost College in Brownville and Texas State Technical College in Harlingen, established in 1926 and 1968 respectively, as well as UTRGV, with campuses in Brownsville and Edinburg (UT system campuses in Brownsville and Edinburg were sunset as the new university was launched). A medical school opened at UTRGV in 2016.

By 2013, South Texas’s share of higher education expenditures had grown to 18 percent, two points shy of its share of the state population. Doctoral programs also increased from three to nearly 60. All told, the region’s institutions of higher education now serve nearly 75,000 students annually.

Of the STBI, Julieta Garcia says, “That money turned things around. Millions of dollars were sent to South Texas for faculty hiring, equipment, libraries and other facilities. Never before had that happened.”

Fighting for an equal share of higher education dollars and greater access to institutions is one thing. Getting students prepared for college and enrolled in it is another. That, in part, became the role of RGV FOCUS—to address obstacles to college readiness and access in the Valley.

Chapter 4

As a project of Educate Texas at the Communities Foundation of Texas (CFT), RGV FOCUS has its origins in a commitment to securing access to higher education for residents of the Valley.

In 2003, CFT launched the Texas High School Project to introduce an early college high school model to the state of Texas. Its goal was to address the low rate of low-income students of color earning postsecondary credentials. Chris Coxon of Educate Texas says the impact of this statewide initiative in the Valley was to decrease the dropout rate and increase college enrollment; however, “it had a very narrow scope,” he says. He explains that the Texas High School Project understood in 2011 that if it was going to have a big impact in such a large state, it would need to select and focus on regions. Ultimately it selected two, North Texas and the Valley.

In 2011, CFT rebranded the project as Educate Texas to acknowledge the broadening of its scope of work and its focus on regions. As part of this broadened scope, Educate Texas sent the RGV’s five college presidents and two district superintendents information on the “collective impact approach” to solving problems. “Institutions in the Valley weren’t acting together as a region at the time. The collective impact approach is a way to promote regionalism,” says Coxon.

The meeting convened by Educate Texas to discuss the possibility of the campuses adopting the approach and working together—and more closely with the school districts as well—“was the first time they had ever been in the same room for a meeting, even though they were all within 60 miles of each other,” Coxon says. “We knew that if we were going to improve college access and completion, we would need to start engaging all the region’s postsecondary institutions in a partnership.” Coxon adds that the early college work “was the foundation for what brought people together” and that “to scale college access and completion work across the region we’d need to do more than look at individual memoranda of understanding between individual districts and individual institutions of higher education for the early college work; we’d need to look at broader collaborations across organizations.”

Coxon’s colleague, John Fitzpatrick, the executive director of Educate Texas, refers to the move also as “an equity play,” acknowledging that the region lagged behind the rest of the state in terms of high school graduation, postsecondary matriculation and graduation. Fitzpatrick adds that there was not—and still is not—a strong philanthropic infrastructure in the Valley, so a good case could be made for creating an investment platform for state and national funders to invest in the region.

Out of that meeting grew a commitment to founding RGV FOCUS and eventually anchoring it within Educate Texas as one of its projects. RGV FOCUS began operations in 2012, committed to changing the message from residents in the Valley from not belonging in higher education to a belief, as Coxon says, “that I am capable: Higher education belongs to me.”

Since 2012, RGV FOCUS partners have implemented several strategies to transform college readiness, access and success across the region now that colleges have become more physically available to its residents. Its vision is that all RGV learners will achieve a degree or credential that leads to a meaningful career, which will enable them to enter new industries—healthcare and technology, in particular— that replace agriculture as the dominant economic engine in the Valley.

Early on, RGV FOCUS demonstrated its power as a convener. In 2014, it gathered four IHEs and 37 schools districts to respond to House Bill 5, a law mandating that school districts partner with at least one postsecondary institution to develop two college prep courses—one for English and another for math. The law was designed to help students meet the state’s college readiness requirements, allowing them to enroll in credit-bearing courses immediately upon graduation. RGV FOCUS staff reports that the RGV was the only region in Texas at that time that responded to the mandate through a collaborative process that included all its IHEs and school districts. That, Educate Texas believes, is the power of collective impact.

RGV FOCUS continues to convene school districts and IHEs to share promising practices in early college (dual enrollment) efforts initiated by Educate Texas. It’s also working with South Texas College to change enrollment practices that have placed too many students in non-credit-bearing courses. And, until the pandemic hit the Valley hard, it was working with LUPE to advance an effort to train parents on the importance of their children taking rigorous coursework.

A major priority of RGV FOCUS has been increased completion rates of the FAFSA and the Texas Application for State Financial Aid (TASFA). 3 “The organization’s focus on financial aid,” says founding director Luzelma Canales, “was a no-brainer because of the high percentage of low-income and extremely poor students in the Valley, and we had data to show FAFSA and TASFA completion rates were so low.”

Deputy director Katherine Diaz notes that RGV FOCUS engaged in FAFSA completion work in the same way it has engaged in other efforts, by “bringing together a collective of folks to solve the problem.” For instance, in 2015, RGV FOCUS convened the financial aid directors from all the IHEs in the valley and asked them to present and defend the process and documents they used to process TASFA aid.

Meeting participants learned they were requiring information that even the state did not, and their numerous forms and processes made it difficult for students to apply to multiple institutions. As a result of the meeting and follow-up conversations, the institutions now share a common form for TASFA completion, which RGV FOCUS has annotated for students, parents and high school and college counselors. It, along with other tools RGV FOCUS has developed, is available for partners and parents on the resource section of its website.4

As it worked with the region’s colleges, RGV FOCUS also led efforts to build the capacity of the region’s nonprofit community to support FAFSA and TASFA completion. It partnered with United Way of Southern Cameron County (UWSCC), LUPE and the Equal Voice Network, a network of nonprofits that coordinate education efforts with parents to educate high school counselors and parents on the distinctions between TASFA and FAFSA and the differentiated needs of DREAMers and U.S. citizens. LUPE regularly helps families complete financial aid processes, including helping parents fill out and file their taxes. And, for a number of years, RGV FOCUS organized “Super Saturdays” for students and their families to visit the college campuses and complete their financial aid forms with the help of trained advisors.

Diaz explains that the effort has built the capacity and will for school districts to take on the Super Saturdays themselves. Since FAFSA completion is one of the metrics on the scorecard RGV FOCUS partners established, Diaz reports that there’s now a Friday Night Lights-like competition among superintendents for FAFSA completion, and they compete together the same way at their annual retreat.

While FAFSA completion has been a major priority for RGV FOCUS, the organization is leading efforts among the region’s school districts to use data to change the narrative about school success in the Valley.

Chapter 5

“Does the racism that exists bother me?” asks J.A. Gonzalez, superintendent of the McAllen Independent School District,

where he is a 23-year veteran and an RGV FOCUS partner. “Of course, it does, but you can’t get stuff done by having a bunch of people feeling sorry for themselves.” Ninety-two percent of students in McAllen are Latino, 72 percent low income. The district reflects the population of the entire Valley. “We have always tried to make sure ethnicity doesn’t dictate achievement.”

“Notwithstanding evidence to the contrary, a major myth lingers that Mexican Americans … do not value education,” write Richard R. Valencia and Mary S.

Black of the University of Texas at Austin, a myth they say is based on deficit thinking that blames victims of systems and not the systems themselves.5 For Rodney Rodriguez, RGV FOCUS’s senior director, that stereotyping was real and oppressive in his youth, with a high school counselor telling him that he wasn’t a good enough student to go to college and should enlist in the military instead (see sidebar below). Without his mother’s encouragement and his faith, he says he likely never would have gone to college and earned a Ph.D.

Rodney Rodriguez, RGV FOCUS’s senior director, realized he could succeed in college when he received a small scholarship that covered tuition at Laredo College. The son of a migrant worker mother who retired as an employee of the Jim Hogg County Sheriff’s Department and a father who worked in construction, he understood what hard work was. When his parents married in 1966, they didn’t want to work in the fields. With $25.00 in their pockets, they headed to Houston, where his dad got a job working the graveyard shift at Maxwell House. “Anglos worked during the day. Latinos at night,” says Rodriguez.

His dad worked the graveyard shift for six years, a brother was born in 1968, and he followed in 1971. The family moved back to Hebbronville, Texas, where his dad spent four years tearing down one house he purchased for $5,000 and built a new one with his own hands using lumber from the house he was demolishing. The family later followed cousins to Ohio, where they worked in the tomato-packing industry; they got tired of it after nine months and returned to Hebbronville flat broke.

Rodriguez’s parents’ hard work enabled him to spend all day in school regardless of where he lived. He loved learning. “My mom was my rock,” Rodriguez says, and she pushed him to get good grades and pursue higher education. A school counselor didn’t think he was doing well enough in school to go to college, so she suggested he join the military, an option he considered worthy but not appropriate for him.

Rodriguez’s college scholarship covered tuition only, so he had to drive 55 miles to and from the school every day. His mom and dad bought him a 1984 Ford Tempo for the daily trip. Sometimes his car broke down, he says, “and I had to stay by the side of the road. Sometimes I couldn’t eat because I’d have to pay for gas. But I made that trip for eight straight years— every day.” At Laredo, he earned associate, bachelor and master degrees. He went on to earn his Ph.D. from Our Lady of the Lake University in San Antonio, Texas, which required a commute of over 280 miles every weekend for five years to attend classes and conduct research. He remembers the thrill in his community when he got his associate degree: “I was the first in my family to get a college degree. You should have seen the party and barbecue.

”Rodriguez returned to his former high school after he received his Ph.D. The counselor who told him he should have joined the military was still working. “She said hello. But she never apologized.

”Reflecting on the experience, Rodriguez wonders why it had to be so hard and why it’s so hard for kids in the RGV today. “I mean, the bills, the car breaking down, worrying about whether I was going to eat, not having money to live in Laredo. It’s still that hard for the kids we’re working for at RGV FOCUS, and that’s why the work we’re doing to prepare them for college and receive financial aid is so important.”

“Everyone has genius in them and can achieve their dreams,” says Gonzalez, who was a schoolmate of Rodriguez’s and shares the faith that they are both “dream-makers for kids. The only thing that we can control is our own education.” The key to executing an education system that does not perpetuate deficit thinking is a foundational belief that RGV FOCUS has about how student achievement data should be used: avoid focusing on achievement gaps across racial groups alone.

In 2013, Luzelma Canales, RGV FOCUS’s founding executive director, convened the leadership team originally formed by Educate Texas to found the organization. The team of 22 representatives from partner school districts gathered to institutionalize asset-based thinking through the use of student data.

Canales says the group “kept in mind that if you look at gaps you’ve missed the opportunity to amplify what’s working for others.” And, she says, “You lose the opportunity to build capacity to bring others along. The traditional way of examining data perpetuates deficit thinking. People shut down when others are pointing fingers at them. We decided we were going to change the narrative.”

They discussed metrics they would use to measure progress and how to create a data dashboard to identify assets and share “bright spots.” Monthly meetings organized by RGV FOCUS always began with one partner sharing a “bright spot,” Canales says.

The group developed 12 metrics to drive the scorecard and a new asset-based narrative. Prepandemic it released a score card showing that 87 percent of RGV students attend an A or B school, as determined by the state’s school rating system, versus 65 percent statewide, 61 percent in Dallas County and 52 percent in Bexar County (home to San Antonio). They also outperformed the state average on eight of the 12 indicators.

The team of 22 representatives from partner school districts developed 12 metrics to drive the scorecard and a new asset- based narrative. Prepandemic it released a score card showing that 87 percent of RGV students attend an A or B school, as determined by the state’s school rating system, versus 65 percent statewide, 61 percent in Dallas County and 52 percent in Bexar County (home to San Antonio). They also outperformed the state average on eight of the 12 indicators.

Each year, RGV FOCUS synthesizes the data and creates a scorecard for each district. It convenes district teams to examine the data and discuss “bright spots.” School districts host leadership team meetings, and the host district kicks meetings off by sharing its “bright spots.” “RGV FOCUS gives us the big picture, but each superintendent wants to be better than the other. So, in our individual teams we’re doing really good thinking and competing with other teams,” says Gonzalez.

While FAFSA completion and proving school districts with data have been major priorities of RGV FOCUS, it has had to adjust priorities as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had an outsize impact on the region due to its high levels of poverty.

Necesitado

Me encuentro, Señor

Ayúdame a ver, yo quiero saber

Lo que debo hacer

Muestra el camino

Que debo seguir

Señor por mi bien

Yo quiero vivir, un día a la vez

Un día a la vez, Dios mío

Es lo que pido de ti

Dame la fuerza para vivir

Un día a la vez

Ayer ya paso, Dios mío

Mañana, quizás no vendrá Ayúdame hoy

Yo quiero vivir, un día a la vez

Tú ya viviste

Entre los hombres

Tú sabes mi Dios que hoy está peor Es mucho el dolor

Hay mucho egoísmo

Y mucha maldad

Señor por mi bien

Yo quiero vivir, un día a la vez

—Canción cantada en el valle

In need,

I find myself, Lord

Help me see, I want to know

What I should do

Show the way

What should I follow

Lord for my sake

I want to live, one day at a time

One day at a time, my God

Is what I ask of you

Give me the strength to live

One day at a time

Yesterday passed, my God Tomorrow, maybe it won’t come

Help me today

I want to live, one day at a time

You already lived

Between the men

You know my God that today is worse It’s a lot of pain

There is a lot of selfishness

And a lot of evil

Lord for my sake

I want to live, one day at a time

—Song sung in the Valley

Chapter 6

“People ask why so many of us are dying. That’s an incredible question to me because the answer is so obvious. It’s poverty,”

says Valdez-Cox. In an article entitled “In the Rio Grande Valley, Death has Become a Family Affair,” the New York Times reports that the death rate for those infected by the virus in the Valley is five percent when it has been at two percent nationally.6 “It’s hit really hard,” Valdez-Cox says. “That points to one thing: the persistent inequality that leads to poverty.”

LUPE reports that some are so poor in the Valley they don’t have money for masks and wear used disposable ones for days. Because large multigenerational families often include older adults in small homes, when one person gets sick, the entire family gets sick. One-third of the residents are undocumented, and more are uninsured. For undocumented residents, the fear of visiting a hospital and being deported is often so great that families must decide whether health outweighs the possibility of family separation. LUPE reports that these fears come because ICE frequently parks trucks outside hospital doors in the Valley, and there have been instances when patients have been handcuffed to beds. The fear of the undocumented stretches to testing clinics, where the worry of being found and deported is substantial as well.

In 2020 and 2021, Valdez-Cox and her LUPE colleagues visited the fields she once worked, distributing masks to a new generation of farmworkers who work closely with each other and live in tiny houses in the colonias. “The thing about the Valley is that we never forget where we came from,” she says.

At the same time, RGV FOCUS and other partners have been advocating for, pursuing funding for and securing internet access, plus paying for hardware and training for families that have not used technologies that support learning before. The organization also repurposed grant funds to make $20,000 contributions to four key partners—including LUPE—to purchase laptops and internet access for employees who themselves live in the under resourced neighborhoods they serve.

RGV FOCUS has repurposed additional foundation dollars to focus on wellness during the pandemic. Dollars originally earmarked for the UWSCC for expansion of its All-In Initiative—an effort to increase the number of low-income, young adults with postsecondary credentials with labor market value in the Los Fresno and Point Isabel independent school districts—are instead being used to address pandemic-related mental health issues. In response to requests by the superintendents of the two school districts, RGV FOCUS sought approval from the funder to repurpose the dollars and facilitated a partnership between UWSCC and UTRGV’s School of Counseling to develop and host mental health webinars for district staff.

Positive results led leaders to conclude more could be done. As a result, RGV FOCUS secured funding from a Texas-based foundation to support the creation of six videos related to the effects of COVID-19-induced stress on adults and middle school and high school youth. RGV FOCUS houses the resources on the COVID-19 page of its website.7

As Rodriguez says, RGV FOCUS needed to shift priorities: “Our priority now is keeping both the children and adults of our region healthy.”

Chapter 7

As RVG FOCUS temporarily shifts priorities due to the pandemic, its staff and partners remain in the business of helping the dreams of the students in the Valley come true through the hard work of all.

That point is reinforced by McAllen’s superintendent, who is clear that dreams don’t come true if people in the Valley sit around feeling sorry for themselves. Instead, he says, the lives of people in the Valley are animated by purpose and effort.

That point is underscored by the life story of Rodney Rodriguez, who drove over 100 miles a day in an old car to earn four college degrees over a span of eight years. It is underscored by Rodriguez’s parents, who worked hard so that he could focus on school. And it is underscored by Juanita Valdez-Cox, who worked in a field to feed the nation as a young girl and ended up leading the Valley’s immigrant rights organization.

But the story of the RGV and RGV FOCUS is not, nor should it be confused as, one in which resilience triumphs over all. The story of the RGV is that there needs to be a bargain between the people of the Valley and those living outside the region’s secondary border. Christina Patiño Houle of RGV FOCUS partner Equal Voice sums up what this bargain should be. “The notion of demanding that communities should be resilient puts the responsibility of overcoming structural oppression on the oppressed,” she says. “It’s a collective responsibility to dismantle systems of oppression. It’s unfortunate that so much pressure is put on underserved regions like the Rio Grande Valley. The notion that if people simply worked harder everything would be okay is offensive and wrong.”

“It shouldn’t have to be so hard,” Rodriguez admonishes, as he thinks about his own path through higher education and the path many of the students RGV FOCUS supports will likely take as RGV FOCUS and its partners push hard to ensure that all the region’s children pursue a postsecondary education. Valdez-Cox contemplates the same challenges, turns to her faith and her memories of César Chávez and Dolores Huerta. She wonders why there are issues of injustice in the Valley and why the question she asked as a little girl when she was working with her family picking vegetables is one that other children still ask 60 years later.

“Mommy and Daddy, why is it that you work so hard and yet we remain so poor?”

As they have for generations, the people of the Valley will continue to take it one day at a time.

“We will continue to take care of our neighbors because we remember where we came from. We will fast and pray for those who do not love us,” says Valdez-Cox. “We are dedicated to nonviolence to address injustice, but that does not mean we are passive. We will continue to work with the oppressed to build their power to address the injustice that impacts their lives. Faith and hope without action will only increase the suffering of the most vulnerable in the Valley, and that’s why we act to address injustice while we pray. In spite of the injustice, we’ll still sing about the beautiful colors of the Valley and the joy of being alive.”

1 An undated online NBC news article, The History of Racism Against Mexican-Americans Clouds Texas Immigration Law, makes the assertion that all the presented facts are the reason many Latino civil rights groups have their origins in the state.

2 The sources of the historical information, data and the table in this and the following paragraphs are articles written by Albert Kauffman, one of the attorneys who argued for the plaintiffs in the MALDEF case. See Effective Litigation Strategies to Improve State Education and Social Service Programs, University of Houston Law Center, 2016 and Latino Education in Texas: A History of Recycling Discrimination in St. Mary’s Law Journal, 2019.

3 Texas offers its own system of financial aid (TASFA). It is available to both U.S citizens and undocumented students.

4 See here for the TASFA toolkits and other resources on the RGV FOCUS website.

5 See Mexican Americans Don’t Value Education!—Myth, Mythmaking, and Debunking, R. R. Valencia and M. S. Black. Journal of Latinos and Education, 2002.

6 See the New York Times article In the Rio Grande Valley Death Has Become a Family Affair.

7 See here for the list of COVID-19 Resources on the RGV FOCUS website.