Tacoma

says community leader Lyle Quasim, reflecting on the rich lives lost to generations of students of color who passed through the Tacoma school district’s doors the last half century.

Quasim is on the board of the Foundation for Tacoma Students (FFTS), the organization coordinating the city’s cradle-to-career education initiative, Graduate Tacoma. Retired after a career that included teaching school for the Black Panther Party, defending Native American fishing rights and serving as a college president and cabinet member as the head of state agencies for two governors, Quasim sits behind his home desk for a virtual interview. On the wall behind him, photos of Malcolm X and Nelson Mandela and commemorations from the Washington State Patrol, Pierce-County Sheriff’s Department, the NAACP and other organizations reflect his aspirations, ideals and life accomplishments. A book on the history of lynching in America is a permanent fixture on his coffee table. Quasim says it prepares him psychologically for going out into the world each day.

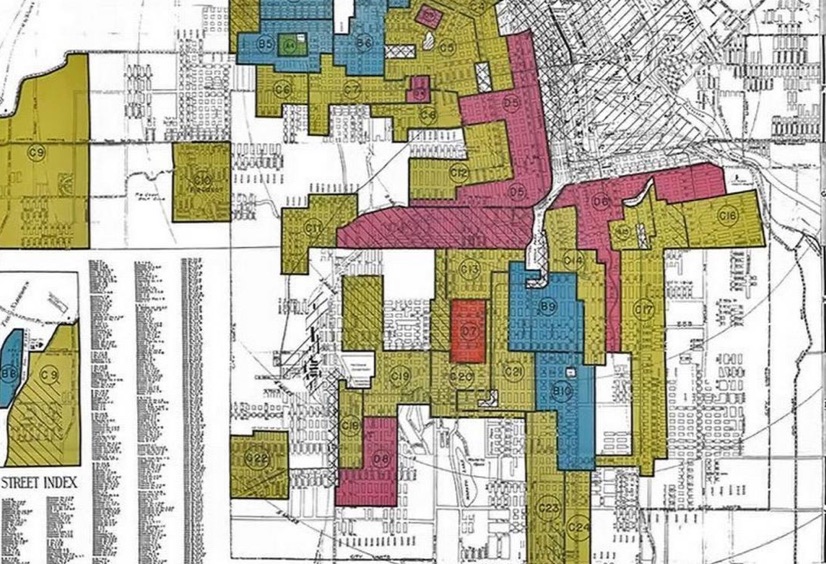

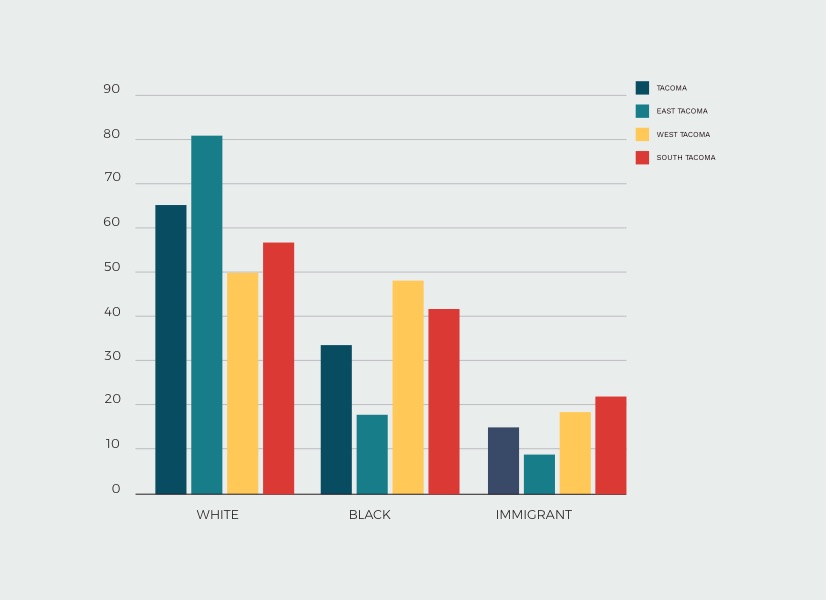

African Americans came to the Pacific Northwest in larger numbers following the Civil War, eager for opportunities they did not have access to in other parts of the country. However, they never enjoyed any sense of parity with white citizenry. As discriminatory barriers increased in the south and east coast from the late 19th century into the first decades of the 20th, discriminatory practices increased their intensity in the west at the same time. Though Black Tacomans were never herded out of the city, they and other people of color and immigrants were isolated in separate parts of town, specifically south and east Tacoma and the Hilltop neighborhood.

Worse to come were discriminatory banking and lending practices fostered by the United States government and directed at citizens in these communities. In the 1930s during the Great Depression…

As devastating as COVID has been, it has perhaps gifted us an opportunity to scrap the usual and reinvent ourselves. The norm is no longer normal, so playing with answers feels safer. We’re not bound by the confines of the way things have always been.

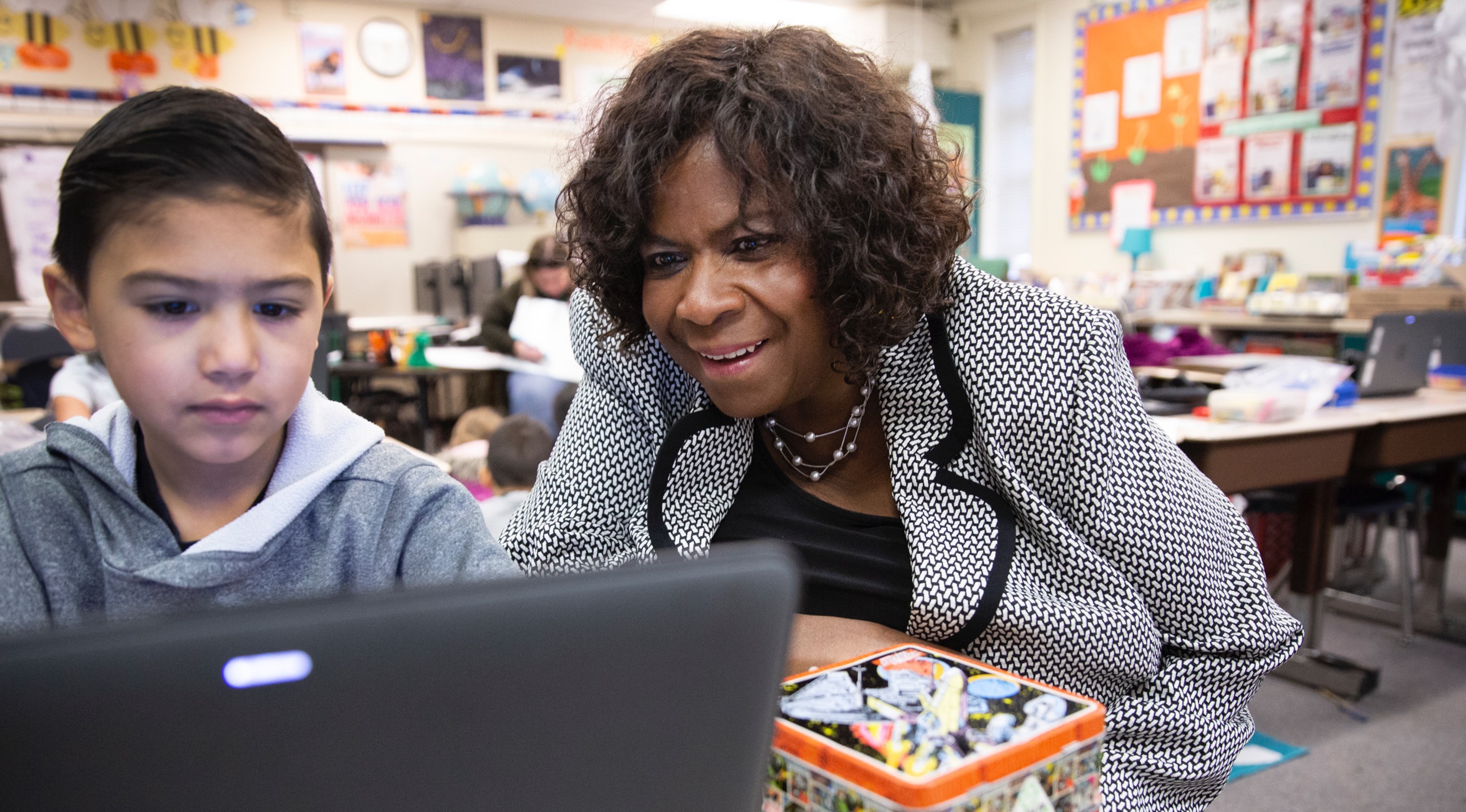

“Blacks in America have always had the mentality that they have to fight, persist and be resilient against systems of oppression. Giving up is not an option,” says Tafona Ervin, Tacoma native, public-school graduate and current executive director of the Foundation for Tacoma Students (FFTS).

In 2016, FFTS refined its longstanding focus on equity and identified children and youth of color explicitly as the target populations for the organization’s work. It worked with partners to shift focus toward south and east Tacoma, the sections of the city most impacted by redlining. Soon thereafter, it announced that in its role as a funder, it would direct its grants for out-of-school time programs toward those parts of the city only. Ervin notes that “in just a year, we shifted significantly the number of programs that were being offered in south and east Tacoma. It was a necessary move because the disparities were so great.”

Graduate Tacoma and its partners have worked where they could to mitigate the pandemic’s devastating impact on Tacoma’s students of color. “Let’s be real,” says Tanya Durand of Greentrike, the city’s children’s museum and Graduate Tacoma partner. “If things were harder for Black and brown families before, don’t you think they’ve gotten worse?” Quasim answers the question affirmatively, but suggests that history has taught communities of color to be more circumspect about the effects of the virus, placing it in the context of just one more calamity in the face of many: “We know the disease impacts Black and brown people disproportionately. But for us, this is just one more damn thing, one more mountain to climb, one more brick in the wall that scars and hurts us.”