Tacoma Refuses To Lose

The We Refuse to Lose series explores what cradle-to-career initiatives across the are doing to improve outcomes for students of color and those experiencing poverty. The series profiles five communities—Buffalo, Chattanooga, Dallas, the Rio Grande Valley and Tacoma—that are working to close racial gaps for students journeying from early education to careers. A majority of these students come from populations that have been historically oppressed and marginalized through poorly resourced schools, employment, housing and loan discrimination, police violence, a disproportionate criminal justice system and harsh immigration policies.

Since early 2019, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has supported these five community partnerships and convened their leaders as a learning community. It commissioned Education First to write this series to share how these communities refuse to lose their children and youth to the effects of systemic racism and a new and formidable foe—COVID-19.

Chapter 1

“We can’t unring that bell,” says community leader Lyle Quasim, reflecting on the rich lives lost to generations of students of color who passed through the Tacoma school district’s doors the last half century.

Quasim is on the board of the Foundation for Tacoma Students (FFTS), the organization coordinating the city’s cradle-to-career education initiative, Graduate Tacoma. Retired after a career that included teaching school for the Black Panther Party, defending Native American fishing rights and serving as a college president and cabinet member as the head of state agencies for two governors, Quasim sits behind his home desk for a virtual interview. On the wall behind him, photos of Malcolm X and Nelson Mandela and commemorations from the Washington State Patrol, Pierce County Sheriff’s Department, the NAACP and other organizations reflect his aspirations, ideals and life accomplishments. A book on the history of lynching in America is a permanent fixture on his coffee table. Quasim says it prepares him psychologically for going out into the world each day.

“In some ways, I can say there’s been a significant evolution in the Tacoma Public Schools. But if time has any value, I look at 50 years of students who have come through this system and who have been discounted and marginalized and who never had opportunities. For them, the die has been cast. Their ability to be full participants in the Tacoma and Washington experience and the experience of America has been marginalized. There is no way to go back to retrieve that.”1

Quasim’s invocation of the past illuminates the direct line between the history of systemic racism and disparities that exist for people of color in our country today, including those who call Tacoma home.

Chapter 2

Tacoma’s history bears witness to its oppression of people of color. Only a decade after its incorporation in 1875, Tacoma was no stranger to organized coercion, cruelty and violence leveled against nonwhites. Like other communities in the Pacific Northwest, it engaged in the wave of anti-Chinese sentiment and violence that swept the region in the late 1800s. Then, opinions authored by Tacoma’s newsmen reflected the organized efforts to terrorize the city’s Chinese citizens. One called on Tacomans to “furnish them with lots on the waterfront, three fathoms below low tide.”2

In October 1885, inflamed rhetoric led to the terror of a white mob headed by Tacoma’s mayor. It raided the city’s Chinatown and force-marched its residents to the train station, herding them onto railcars bound for Portland. Mobs later burned two Chinese settlements to the ground.3

African Americans came to the Pacific Northwest in larger numbers following the Civil War, eager for opportunities they did not have access to in other parts of the country. However, they never enjoyed any sense of parity with white citizenry. As discriminatory barriers increased in the South and East coast from the late 19th century into the first decades of the 20th, discriminatory practices increased their intensity in the West at the same time.4 Though Black Tacomans were never herded out of the city, they and other people of color and immigrants were isolated in separate parts of town, specifically south and east Tacoma and the Hilltop neighborhood.

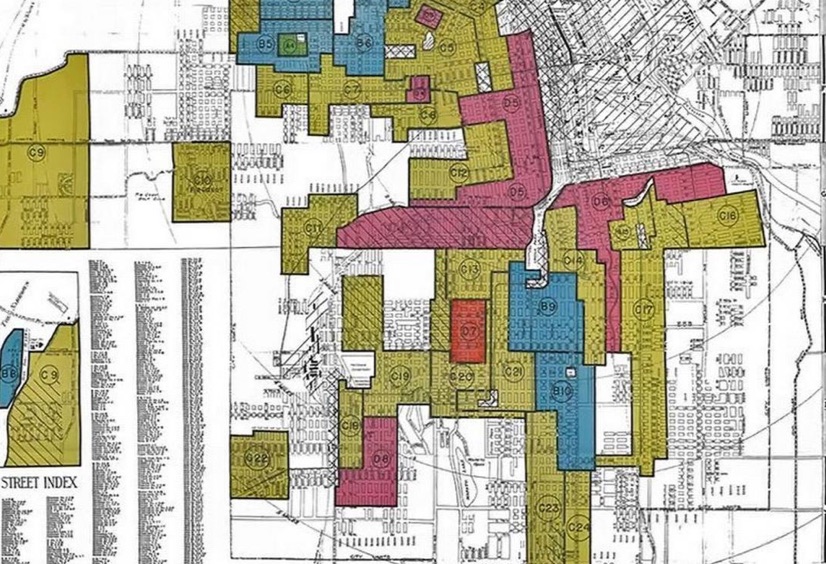

Worse to come were discriminatory banking and lending practices fostered by the United States government and directed at citizens in these communities. In the 1930s during the Great Depression, the federal government decided to nurture home ownership by guaranteeing long-term loans for middle- and working-class families. It established the Home Owners Loan Corporation, which created what came to be called “Redline Maps” to provide guidance to banks about neighborhoods they should consider safe for loans. Exclusively white communities, designated as green and blue zones on the maps, were deemed suitable for investments; yellow and red zones had “undesirable populations” or were subject to the “infiltration of a lower-grade population” and were considered “hazardous” for lending. The practice meant that banks made loans only to homebuyers in the white neighborhoods.

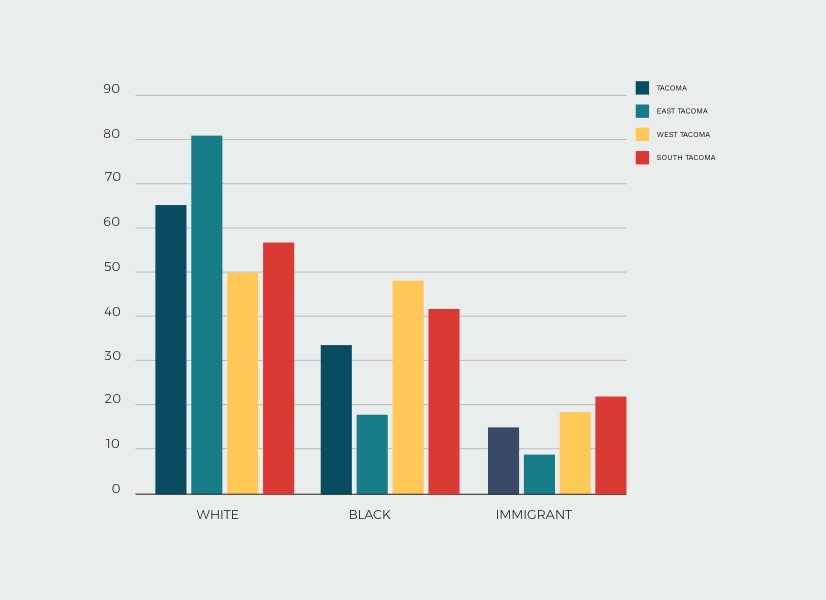

The redlined maps developed for Tacoma show the bulk of South and East Tacoma as yellow and red zones. In a 2018 article headlined, “How racism kept black Tacomans from buying houses for decades,” The News Tribune articulated the dire consequences of the American banking industries’ perspective that “nothing downgraded an otherwise acceptable neighborhood like the presence of black families.” Today, those living in these neighborhoods earn far less, are less likely to have a college degree or own a home and have lower life expectancies than those living in what once were deemed better neighborhoods. Economically, the practice denied Black families financial security and generational wealth; national data reveal that white families have almost 10 times more net worth than Black families.5

Data presented by Tacoma’s Office of Equity and Human Rights make obvious the impact the broken and racist American housing system has had on Tacoma’s citizens of color. The office “scores” equity for areas among each of the city’s council districts, combining multiple indicators such as education and livability to place each of them on an equity index from low to high. In South and East Tacoma (areas formerly identified as yellow and red zones), the equity indicators in 2020 don’t add up to opportunity for the more heavily minoritized and immigrant communities living there now (see below).

“Housing is one of the notable ways families prosper and transfer that prosperity to the next generation,” notes Michael Mirra, executive director of the Tacoma Housing Authority, a Graduate Tacoma partner. “The racial inequities of the nation have been baked into housing markets from the start. This ongoing history helps explain disparities we now see—wealth, health, life spans, educational attainment, employment and earnings. At the present rate, it will take generations to outgrow this history.”

The history of racial oppression, including but not limited to housing discrimination in Tacoma, goes a long way toward explaining why inequities in student opportunities and outcomes in education exist, suggests Brian Boyd, a local foundation executive and funder of Graduate Tacoma. “You can nod your head and say, ‘Yeah, people achieve differently because of race.’ This of course is a racist idea,” Boyd says. “Or you can look and see broken systems and policies. Never before have more people understood that.”

Chapter 3

Graduate Tacoma refuses to lose more generations of color to racist systems. “Blacks in America have always had the mentality that they have to fight, persist and be resilient against systems of oppression. Giving up is not an option,” says Tafona Ervin, Tacoma native, public-school graduate and current executive director of the FFTS.

For generations, Tacomans of color have persisted in their fight not only against systems that produce pernicious gaps in education outcomes but also their effects. A decade ago, the historic gap in on-time graduation rates between whites and students of color weighed the community down.

In 2010, a USA Today headline called Tacoma high schools “drop-out factories.” The ignominy of Tacoma’s 55 percent overall graduation rate was exceeded only by the even more shocking 33-point gap in the graduation rate between Black and white students.

The Graduate Tacoma movement was forged in this national outcry for change. Hundreds of Tacomans—residents, educators and representatives from foundations, faith- and other community-based organizations (CBOs), business and labor interests and the early learning community—came together to establish FFTS to coordinate what is now a coalition of nearly 350 organizations focused on increasing graduation and college completion rates. In 2010, the partners established a clear two-part goal: By 2020, the graduation and college completion rates for Tacoma Public Schools (TPS) would increase by 50 percent.

Graduate Tacoma’s first executive director, Eric Wilson, shares the thinking behind the movement’s origins: “Schools can’t do it alone. And no single program, organization or institution acting in isolation can achieve the large-scale change our students need and deserve.” Boyd attributes the origins to the scrappiness of the citizens of the self-proclaimed “Grit City” who are not unfamiliar with bad-news headlines like the ones that came in 2010. “We turned these qualities into the fuel needed to galvanize community spirit and will and focused on creating better outcomes for all Tacoma students, with a pronounced emphasis on shrinking, and in some cases eliminating, achievement gaps based on race and family income levels.”

Well before 2020, the Graduate Tacoma movement achieved its first goal: By 2018, the graduation rate increased to 89 percent, and the rates between Black and white students and between Latino and white students closed to two percentage points. Superintendent Carla Santorno (who took office in 2012 after serving as deputy for two years and is a member of Graduate Tacoma’s board) says that there is no silver bullet to closing opportunity and achievement gaps. What is required, she says, is community-wide engagement: “If the only people engaged are educators, then it’s not going to work. If there is an invested group of foundations, faith-based organizations, nonprofit groups and others, that’s what’s going to work.”

Graduate Tacoma created space for discussion and nourished community-wide buy-in and investment in improving the graduation rate and closing gaps based on race. Its first step was to establish the ambitious graduation and college completion goals (the goals were later adopted by the school district and the city). Then Graduate Tacoma expanded ownership for the graduation problem well beyond its own, the district’s, the city’s and its initial partners’ ranks, making the goal of high school graduation a priority from the grass roots to its tops. Nonprofit organizations, businesses, postsecondary institutions and faith-based organizations joined three CANs coordinated by FFTS staff and focused on early learning and reading, out-of-school and summer learning and college access and completion. A STEAM-focused and advocacy-focused CAN formed later.

Focusing on high school student success, attending and persisting through college and parent and family engagement, one of Graduate Tacoma’s CANs, the Tacoma College Support Network, concentrated on making college enrollment and completion a realistic and important aspiration—not a pipe dream. Members of the CAN worked on increasing scholarship and FAFSA/WASFA “sign ups,” improving family financial literacy, assisting families in planning activities such as campus visits and oversaw the translation of documents for non-English-speaking families. They partnered with every higher education and college access and completion organization in Pierce County to focus intentionally on boosting enrollment and persistence and completion rates and mailed college and career toolkits to all students in grades 9–12.

Acknowledging that it’s never too early to start preparing students for college access and completion, Graduate Tacoma’s early learning CAN engaged the grass roots. Its partners created neighborhood libraries in South and East Tacoma and helped barbers turn their shops—key gathering places for communities—into language-rich learning environments filled with books, discussions about them and conscious expressions by adults of the connection between reading, college and a good life.

All told, perhaps the most important accomplishment of Graduate Tacoma is the change in the city’s college-going ethos. Santorno tells the story of seeing thousands of “Graduate Tacoma” signs planted in yards across the city around the time of Graduate Tacoma’s launch: “Tacoma was a blue-collar town, so college wasn’t considered a big deal by everyone. What Graduate Tacoma did was set the tone and build the college-going culture. It got the word out about the importance of graduation,” she says. “And it did a lot of things we couldn’t do, helping students with FAFSA forms and securing scholarships and financial aid. They funded and expanded our efforts to put kids on buses to visit colleges.”

Quasim, like his fellow board members, gives a large amount of credit to the hard-working students, teachers and administrators in TPS. “They’re the ones who really have sweat on them.” But they needed help, he adds, acknowledging the important role Graduate Tacoma played: “The fact is if students, teachers, principals and administrators could have done it without Graduate Tacoma, they would have done it by themselves. But they didn’t.”

“It was all hands on deck,” Boyd says, summing up why Tacoma was able to increase its graduation rate overall and close gaps between white students and students of color.

Chapter 4

Data underscoring racial injustice moved Tacoma’s cradle-to-career effort to focus more explicitly on equity of opportunity in south and east Tacoma. In 2016, FFTS refined its longstanding focus on equity and identified children and youth of color explicitly as the target populations for the organization’s work. It worked with partners to shift focus toward South and East Tacoma, the sections of the city most impacted by redlining. Soon thereafter, it announced that in its role as a funder, it would direct its grants for out-of-school time programs toward those parts of the city only. Ervin notes that “in just a year, we shifted significantly the number of programs that were being offered in South and East Tacoma. It was a necessary move because the disparities were so great.”

FFTS targets other efforts in these areas of the city as well. For example, it operates a Building Connections early learning professional development program to bring together primary caregivers, early learning educators (including in-home providers) and elementary school teachers. FFTS convenes these groups in South and East Tacoma to ensure that transportation is not a barrier to residents’ participation.

Reflecting on this shift of emphasis, Quasim recalls how at some point “there was an awakening on the board but not a kumbaya moment,” noting that the clear articulation of target populations was less an impassioned commitment and more a pragmatic understanding that to move the ball on the graduation rate, the focus had to be on students of color. Santorno agrees: “If we were going to meet our graduation goals, we had to focus on the kids who weren’t making it. That’s how the shift happened.”

Ervin notes that the shift reflected a change in focus on equity from the general to the specific. “Historically, there was an interest in students of color but at the very aggregate level,” she says. However, she believes that Graduate Tacoma raised the bar high above its initial equity work when it began explicit community-wide communications to identify where in the Tacoma community and among what populations racial inequities existed and what supports these populations needed. To support these communication efforts, it disaggregated data and created a central data warehouse to make sense of, create visualizations for and synthesize and simplify the data for public consumption. It also hosted conversations about the data and community needs exposed by them to help funders make bold and ambitious investments directly targeted to subpopulations of students in South and East Tacoma.

“We were the only organization aggregating all the data and putting it into a single narrative in one document to help people make sense of it and suggest what we as a community should do about it,” Ervin says. “We’ve helped more people get to ‘the why’ of the work.”

In the last two years, FFTS’s board has become more aggressive about making its leadership for equity explicit. Among other public statements, it acknowledges on the organization’s website that “equity recognizes that we do not all start from the same place because of advantages and barriers that exist” and that FFTS “seeks to correct the imbalance for the most marginalized and minoritized populations.” It has also articulated its commitment to “dismantling structural and institutional racism and systems that result in oppression.”7

Within its own shop, FFTS monitors how it resources subpopulations, tracking whether its vendors include women and businesses of color and where its board members reside or do business. For one cohort of Graduate Tacoma partners, FFTS recently published a Racial Equity Organizational Assessment, a tool to spur progress toward equity along a continuum of specific indicators that evidence equitable practices and commitments.

Expressing the leadership role Graduate Tacoma has taken to secure greater equity in Tacoma, Ervin says, “Hopefully we’re helping our partners in the community understand that focusing on equity as an organization doesn’t just mean doing one thing and then being done with it. There’s just so much to do.”

FFTS’s explicit focus on equity for Black and Latino students positioned it for the unexpected: a global pandemic that would shut Tacoma down and exacerbate and magnify inequities for students and families of color.

Chapter 5

COVID-19 underscored the importance of the collective action infrastructure Graduate Tacoma and its partners built as it forced organizations to be flexible and efficient. Graduate Tacoma and its partners have worked where they could to mitigate the pandemic’s devastating impact on Tacoma’s students of color. “Let’s be real,” says Tanya Durand of Greentrike, the city’s children’s museum and Graduate Tacoma partner. “If things were harder for Black and brown families before, don’t you think they’ve gotten worse?” Quasim answers the question affirmatively, but suggests that history has taught communities of color to be more circumspect about the effects of the virus, placing it in the context of just one more calamity in the face of many: “We know the disease impacts Black and brown people disproportionately. But for us, this is just one more damn thing, one more mountain to climb, one more brick in the wall that scars and hurts us.”

Indeed, the disease hit Pierce County’s communities of color at far greater rates than their population levels. Latino and Black residents account for 11 percent and seven percent of Pierce County’s population while, according to health department reports, they make up 23 and 11 percent of confirmed cases respectively. Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander residents make up only 1.6 percent of the county’s population, but nearly six percent of cases.8

Santorno’s firsthand accounts are striking. “I didn’t see how huge a food desert Tacoma was before [the pandemic]. TPS and its partners have now delivered more than one million meals,” she says. “All of the economic factors that school districts ameliorate—feeding kids, giving them access to school supplies, transportation, the internet and sometimes even housing—COVID has shown us what barriers to learning they are.”

Concern for graduating seniors was especially heightened in the spring and summer of 2020. The challenge for Graduate Tacoma and its partners was two-fold: getting seniors across the finish line for high school and keeping them on course to pursue their postsecondary plans.

The collective-action infrastructure Graduate Tacoma and its partners spent 10 years building proved to be invaluable. Since early 2019, as part of its work supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Graduate

Tacoma has been convening a postsecondary access and completion work group made up of organizations already participating in Graduate Tacoma’s postsecondary-focused CAN. Graduate Tacoma enabled the community to set the vision for this work group: It would embark on a year-long effort to create cross-organization, collaborative, systems-level structures to improve coordination among members, increase focus on serving Tacoma’s most acutely minoritized students and ultimately improve credential attainment rates for them.

Graduate Tacoma deputized two organizations—Degrees of Change and the College Success Foundation—to act as intermediaries for the group. Tim Herron—executive director of Degrees of Change, a national nonprofit based in Tacoma focused on preparing diverse, homegrown leaders to succeed in college and use their degrees to build more equitable communities—says, “Tafona [Ervin] called and asked us to take on a more formal role as an intermediary for Graduate Tacoma’s college access and completion work group. While FFTS is the backbone for Tacoma’s collective impact work, they’ve invited us to be the vertebrae for college success.”

The pandemic required the working group, Degrees of Change and Graduate Tacoma to alter course quickly. With Graduate Tacoma’s backing, Degrees of Change leveraged long-time relationships and convened a broad group of 25 leaders from TPS, college access support nonprofit organizations and college-based programs. The group crafted a plan for the “What’s Next TPS Senior Check-In Initiative.” Degrees of Change created an online check-in survey to assess student postsecondary plans that was distributed and promoted to all district seniors through multiple channels. As responses came in, the platform Degrees of Change created made data available immediately to designated staff from high schools, college access CBOs, the nine higher education institutions in Pierce County and all the state’s four-year colleges.

Partners matched students who were not participating in a college access program with volunteers from access organizations. The volunteers found that the vast majority of students needed help with scholarships—though there were other needs—and connected them to college representatives. DJ Crisostomo, one of the “Avengers,” as the college access professionals engaged in this effort call themselves, notes that most of the 28 students he worked with were from South and East Tacoma and that he made sure they had information to make informed decisions about financial aid, reminding them that students of color frequently have more loan debt than white students.

“As devastating as COVID has been, it has perhaps gifted us an opportunity to scrap the usual and reinvent ourselves. The norm is no longer normal, so playing with answers feels safer. We’re not bound by the confines of the way things have always been.”

While disappointed that the effort reached just under a quarter of the district’s seniors, Herron sees the potential that the project opened for future collaboration. “We started three weeks too late,” he says. “But we’ve asked ourselves, ‘Why didn’t we do this before?’ ” The organization and its partners are already discussing with the district how in the upcoming years they can collect these data for students well before the end of senior year, making them part of the comprehensive data collection process that students already go through.

“This is an opportunity for students in the future to opt in to a data system that extends beyond high school graduation,” Herron says. “There’s a huge need for a real-time, student-level data system that connects high schools, CBOs and postsecondary institutions to share actionable data as students leave school districts and continue to need support for college success.”

Chapter 6

Among FFTS staff, board members and partners, there is a sense of optimism and a call to action because there is still “so much to do, so much distance to travel”. Optimism is certain for FFTS and its partners. But that optimism is tempered by its understanding of the daunting task of unravelling historic systems of oppression that have denied opportunities to children of color for centuries. Holly Bamford Hunt, the FFTS board president, acknowledges the impacts as she speaks about feeling hopeful and inspired by the collaborative efforts of Graduate Tacoma and its partners to address “the disproportionate mental and physical health, criminal justice, food, financial, housing and education equity impacts upon Black and brown students and their families.”

Funding partner Brian Boyd says he’s hopeful because he’s “never seen a time in [his] professional life where so many people want to be associated with and see their energies focused on racial progress.” But he reminds Tacomans that the work “remains difficult and painful,” noting that TPS and its partners in the Graduate Tacoma movement accomplished a tremendous amount by raising the graduation rate but that “it’s not that Tacoma can look at all the indicators we track and brag about them, particularly at the rate of college enrollment and persistence.”

Quasim recognizes the hard work that lies ahead for Graduate Tacoma after successfully meeting its high school graduation goals, refusing to rest on those laurels. He knows the pain of generations—both past and present. “It’s fine if people have a sense of satisfaction about the graduation rate. I’m not going to take that away from them,” he says. “But if we say we’re focused on cradle to career, then let’s focus on cradle to career. We still aren’t getting Black and brown students in Tacoma postsecondary degrees and into good jobs. There’s no reason for me to go to a party and celebrate yet.”

Disproportionate impacts and pain remain acute in Tacoma’s Black community. In fact, they are elevated. Less than two months before the murder of George Floyd, the community confronted the death by asphyxiation of a 33-year-old Black man, Manuel Ellis, at the hands of the city’s police, an act for which Tacoma’s mayor called for the firing and prosecution of the perpetrators.9

In an open letter to the Tacoma community following Floyd’s murder, Ervin shared her hurt and anger about “yet another act of racism against Black and Brown people in America” and her despair about needing to prepare her own young sons for a world in which “it has already been made up in some people’s minds that two amazing, sweet, smart, giving, kind, thoughtful boys are a threat, suspects, unworthy, less-than.”

Yet refusing to lose, Ervin issues a call to action to the community, naming the need for white allies and friends, especially those with privilege and power, to “stand up and demand actions against systemic racism.” In the midst of her community’s pain, she plants Graduate Tacoma’s flag firmly in the ground, stating its unapologetic commitment to becoming an anti-racist organization focused on children marginalized by race and poverty and calls on her partners and other organizations to plant their own flags in the same ground of anti-racism.10

“It’s time for white people to take the lead in this fight for a more equitable future,” she says. “Those of us of color are beyond exhausted in professing the systemic racism that persists in our nation.”

1 Lyle Quasim and all the individuals quoted in this text were interviewed in July and August 2020.

2 See Industrialization, Class, and Race; Chinese and the Anti-Chinese Movement in the Late 19th-Century Northwest, Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest, University of Washington and Witnesses to Persecution, The New York Times, 2007.

3 See Industrialization, Class, and Race; Chinese and the Anti-Chinese Movement in the Late 19th-Century Northwest, Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest, University of Washington and Witnesses to Persecution, The New York Times, 2007.

4 See African Americans in the Modern Northwest, Center for the Studies of the Pacific Northwest, University of Washington.

5 See How racism kept black Tacomans from buying homes for decades, The News Tribune, August 10, 2018. See also A ‘Forgotten History’ of How the U.S. Government Segregated America, NPR, May 3, 2017. Information on redlining in this and the preceding paragraph come from these sources.

6 See From ‘dropout factories’ to record-high graduation in Tacoma, Washington, StriveTogether, August 2, 2017.

7See landing page of Foundation for Tacoma Students website.

8 See The Coronavirus is hitting Pierce County communities of color hard, health data shows, The News Tribune, May 18, 2020.

9 See Tacoma Mayor: Officers Who Arrested Manual Ellis Should Be Fired and Prosecuted, NPR, CPR News, June 5, 2020.

10 See Open Letter: Put Equity First and Become an Anti-Racist Organization, Tafona Ervin, Graduate Tacoma, June 1, 2020.