Chattanooga Refuses to Lose

The We Refuse to Lose series explores what cradle-to-career initiatives across the country are doing to improve outcomes for students of color and those experiencing poverty. The series profiles five communities—Buffalo, Chattanooga, Dallas, the Rio Grande Valley and Tacoma—that are working to close racial gaps for students journeying from early education to careers. A majority of these students come from populations that have been historically oppressed and marginalized through poorly resourced schools; employment; housing and loan discrimination; police violence; a disproportionate criminal justice system; and harsh immigration policies.

Since early 2019, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has supported these five community partnerships and convened their leaders as a learning community. It commissioned Education First to write this series to share how these communities refuse to lose their children and youth to the effects of systemic racism and a new and formidable foe—COVID-19.

Chapter 1

Never underestimate the power of loving kindness:

random or planned acts of goodwill, compassion or charity delivered by regular citizens or employees of organizations whose missions are to help people get a leg up. Chattanoogans are known for their loving kindness and commitment to transforming the individual lives of their community’s residents. Sarah Morgan, president of the Benwood Foundation, a founding partner of Chattanooga 2.0, the city’s cradle- to-career community partnership[1], has seen it too: “Chattanooga is a very generous community,” she says. “People are willing to give sacrificially to help others.”

Chattanooga has long been seen as one of the more generous communities in the United States. A city- by-city study in 2012 ranked it as one of the most charitable municipalities in the country, with residents giving away almost two times more to public charities and religious groups than the average American.[2] Magdalena Perez (Maggie), a sophomore at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga (UTC), knows the city’s spirit of generosity well. She says she’s still in college because of it. Born and raised in Chattanooga, Perez is a graduate of Chattanooga’s East Ridge High School and a first-generation college student whose father never attended school in his native Mexico. She pays in-state tuition rates and receives federal financial aid—but that wasn’t always the case. Perez’s first experience with higher education was to receive a bill for out-of-state tuition and notices she’d been denied federal financial aid. She has no idea why her lifelong residence in Tennessee was overlooked but understands that her denial of financial aid resulted from a convoluted set of circumstances—common for immigrant families—she could not untangle by herself to the satisfaction of federal authorities.

Launched in 2015, Chattanooga 2.0 is Hamilton County, Tennessee’s cradle-to-career partnership, a coalition to improve education and workforce opportunities for all residents of the county. It has two goals: (1) doubling the percentage of graduates from Hamilton County Schools who obtain a postsecondary degree or credential, from 30 to 60 percent by 2025 and (2) increasing the overall percentage of adults in Hamilton County with a college degree or technical training certificate from 38 percent to 75 percent by 2025. To attain these goals, Chattanooga 2.0 partners (including school district, nonprofit, philanthropic, business and higher education leaders) are focused on addressing racial and socioeconomic disparities that will make it difficult for Chattanooga to achieve its goal of being “the smartest city in the South.” Chattanooga 2.0’s executive committee is developing a new strategic plan to launch in 2021 as it continues to pursue its original strategies focused on early learning, teacher and principal effectiveness, college readiness and completion and the reengagement of adults in postsecondary training. The Chattanooga Area Chamber of Commerce, Public Education Fund (PEF), the Benwood Foundation and the Hamilton County Schools are founding partners. Chattanooga 2.0, the organization that bears the name of the movement, serves as the backbone organization for the cradle-to-career initiative.

A trip to the financial aid office to try to change her tuition status yielded no results except tears of frustration. It was a stranger, a UTC faculty member passing through the office at the time, Perez says, who saw her sobbing and provided the guidance she needed to resolve the situation in the admissions office. “I don’t know what I would have done without her,” Perez adds.

Her relief was short-lived, however. Several efforts at the university’s financial aid office failed to secure the aid for which she was eligible and left her feeling like she “wasn’t meant to be at the university.” Into her life came Lauren Bensman, a College Advancement Mentor (CAM) employed by the Public Education Foundation (PEF), a partner in the Chattanooga 2.0 coalition.

Each of the ten mentors facilitate the transition of students from high schools with the highest concentrations of students of color in Chattanooga’s metro area to two- and four-year colleges and help them persist through the first two years.

Bensman took Perez back to the financial aid office. After what Bensman calls “an extremely emotional and long day spent meeting with a number of officials,” they got the solution they were looking for. “She kept meeting with people until things got fixed,” Perez says. “I cry every time I talk about her because she’s done so much for me.”

Bensman credits Perez’s persistence as “an amazing young woman” for the resolution of the matter but notes that her steadfast refusal to give up is the exception, not the rule, in the face of so many obstacles. Many students who face similar obstacles eventually conclude that they don’t belong. She says, “For every one Maggie, there are 10 students who don’t make it. There are so many hurdles that they eventually get the sense they don’t belong and leave.”

PEF is a founding member of the 2.0 coalition, a partner to the 2.0 organization and the “managing partner” of high school and postsecondary work under the 2.0 partnership’s broader initiative. PEF is a nonprofit community-based organization that for over 30 years has provided professional development to teachers and principals to increase student achievement and robust learning experiences for students so they can become the first in their families to go to college. PEF manages the college advancement mentor program featured in this profile.

That sense of not belonging persists for many of Chattanooga’s students on their journey from ninth grade through college. The massive data base co-constructed by PEF, Hamilton County Schools, Chattanooga State, and University of Tennessee at Chattanooga allows the partners to track the progress of all public school students from kindergarten through postsecondary education. It shows that students in schools with the highest percentage of students of color drop out at alarming rates: 33 percent while in high school, 23 percent in the summer after high school graduation and 27 percent between their enrollment in and completion of postsecondary programs.[3]

Loving kindness—as powerful as it may be in Chattanooga and as helpful as it was for Maggie Perez—is just not enough.

Chapter 2

“There’s a lot of loving kindness but not enough urgency in Chattanooga,”

says Edna Varner. She’s been waiting a long time for Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that racial segregation of children in public schools is unconstitutional, to deliver on its promise. Varner works for PEF, helping it improve teacher preparation and diversify the teaching ranks through its residency program. Retired after decades as a teacher and high school principal in Chattanooga, Varner started kindergarten in the city in 1955, the year after the Supreme Court’s decision.

While her parents knew they couldn’t eat at the same lunch counters, drink from the same water fountains or shop at the same stores as white people in the city, they believed the greater opportunities afforded children at the city’s all-white schools awaited their own. By the time Varner graduated from high school in 1968, however, she was still attending an all-Black school, despite the fact that in 1960, a federal court had declared Chattanooga’s school system in violation of the Supreme Court’s decision, placed it under its supervision and required it to develop a plan to integrate its schools.

In 1971, the court found Chattanooga’s efforts to desegregate schools inadequate. Like those in other cities, Chattanooga’s “freedom of choice” plan placed the burden of integrating schools on Black families, requiring them to make an affirmative choice to desegregate all-white schools. A new court order put the impetus on the Chattanooga board of education, requiring it to implement a plan that included busing.

The order precipitated fierce white resistance that included white flight to the suburbs, arguments that the school district did not have enough money to implement a busing program and pursuit and receipt of a lower court ruling to prohibit tax increases for busing (no systematic busing system was ever implemented).

By 1986, the federal court ruled that the school district had complied with the 1971 order in part because it decided that the board of education had done all it could to integrate schools in a city with profound residential segregation (see sidebar on residential segregation). Still, 70 percent of the district’s elementary schools had populations that were either at least 70 percent Black or 70 percent white. Five were either all Black or all white. The same pattern held in middle and high schools.[4]

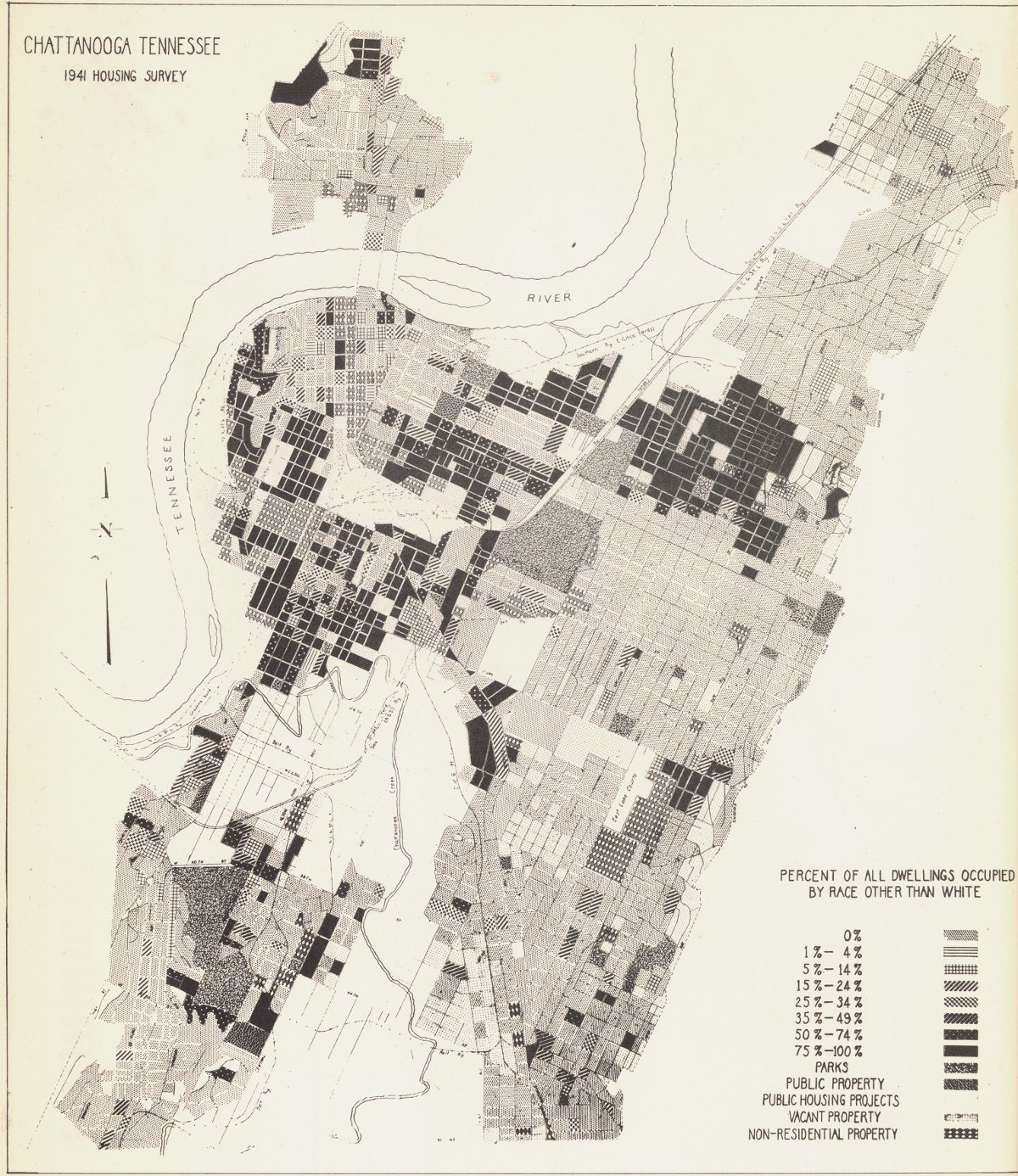

Chattanooga’s residential segregation is not peculiar to the city or the region. It is endemic across the United States and a root cause of race- based inequities in outcomes and opportunities in health, education and employment. See the Tacoma and Buffalo profiles in the We Refuse to Lose series for the factors that contributed to residential segregation in Chattanooga as well. They include redlining, the U.S. government’s sponsorship of racist lending practices that prevented people of color from securing home loans and Black families from building generational wealth; restrictive covenants that prevented people of color from moving into white neighborhoods; urban renewal that bulldozed neighborhoods to make way for highways and city amenities; government-funded white flight to the suburbs; and gentrification. Formerly redlined neighborhoods in Chattanooga include Hill City, Westside, Alton Park, Clifton Hills and East Chattanooga. Other areas, including Cameron Hill, North Chattanooga, Downtown and Southside, have been gentrified through public and private investments. Urban renewal projects such as the Golden Gateway renovation project, which authorized construction of the US-27 Interstate exchange, resulted in the destruction of the Ninth Street neighborhood, a once vibrant cultural, business and residential hub for the Black community.Census data shows that 11 neighborhoods (census tracts with poverty levels of 40 percent or greater) were 73 percent African American in 2015.

Sources: The Tennessee State Library and Archives Mapping the Destruction of Tennessee’s African American Neighborhoods; the Chattanooga NAACP’s The Unfinished Agenda: Segregation & Exclusion in Chattanooga, TN and The Road Towards Inclusion; and the University of Tennessee UTC Scholar’s From the hallways to the courtroom: struggle for desegregation in Chattanooga, Tennessee 1954-1986.

The Chattanooga City Schools merged with the Hamilton County district in 1995, a move that the city’s Black community opposed.[5] The merger of the Black-majority city school district with a nearly all-white county district forced renewed conversations about race, says Jesse Register, the superintendent hired to lead the new district in the late 1990s: “Right from the start we had to talk about Black and white issues and integration of schools.”[6] Register’s efforts to address segregation and inequities across the new district began with rezoning and magnet programs and, later, efforts to reconstitute nine elementary schools the state had identified as among its 20 lowest-performing schools. The schools made dramatic progress that was recognized nationally for close to a decade, but when philanthropic support ended in 2011, the performance of the schools trended downward. The Chattanooga Times Free Press reports the schools saw improvements that did not last in part because they exacerbated tensions with white county residents who expressed concerns that “they weren’t getting a fair shake.” [7]

Though city and county residents continued to share a common tax obligation in the first decade of the 21st century and into the second, their children learned in a number of schools that remained racially isolated, prompting James Mapp, the NAACP member who originally brought suit against the Chattanooga school district, to say on the 60th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision, “The shame of it is that parts of Chattanooga are worse than [they were] before.”[8] Varner says simply, “Separate was still unequal.”

Varner’s point was not lost on civic leaders when they launched Chattanooga 2.0 in 2015. Leaders included those involved in Register’s work—PEF and the Benwood Foundation—but got an added boost from the Chattanooga Area Chamber of Commerce, which joined them as a founding partner. The organization’s inaugural report documented the fact that Black students were 33 times more likely than the county’s white students to attend schools ranked in the bottom 5 percent of all Tennessee schools. For each Black student enrolled in one of the state’s highest- performing schools, seven were relegated to one of the lowest performing.

Chattanooga 2.0’s founding report observed that these inequities reflect the confluence of residential segregation and school zoning: “Much of the inequality is based on where students live, with students from different neighborhoods receiving vastly different educational experiences. In five of our high school zones, at least half of the schools in the zone are in the bottom quarter of the state in student achievement: Brainerd, East Ridge, Hixson, Howard, Tyner. Being born in these zones virtually guarantees that the bulk of a student’s educational experience will occur in schools where students are not learning to read or do math on grade level.”[9]

The report also documents that the inequities existing in high school extended into Chattanooga’s institutions of higher education, Chattanooga State Community College and UTC. In 2015, whites accounted for at least 75 percent of the population at both institutions. Latinos made up under 5 percent of the student body at both institutions, while Blacks accounted for 10 percent at UTC and 15 percent at Chattanooga State. The six-year graduation rate for all students at Chattanooga State was just under 25 percent in total; however, it was only 5.5 percent for Black and 20 percent for Latino students. Racial gaps existed at UTC as well, with a 53.2 percent graduation rate overall that fell to 40 percent and 50 percent for Black and Latino students, respectively.[10] (See page 19 for the college advancement work Chattanooga State has been making since 2015’s report—and its improved retention rates.)

For more than 60 years—from the early promise of Brown v. Board of Education in the 1950s to the end of a federal court order designed to fulfill it in 1986, through a school district merger in the 1990s and efforts in the early 21st century to integrate schools and bring greater equity of opportunity and outcomes to students of color—Edna Varner and the generations of students of color who followed were still waiting when Chattanooga 2.0 launched in 2015. A growing population of Latino students—in 2020, the population of students stood at about 17 percent— whose families had come to the region for employment opportunities and who were isolated in many of the same schools, joined the wait.

Chattanooga 2.0 and its partners have come to believe that bringing an end to that wait requires taking at least two steps. First, it must address a cultural barrier in the community: its reticence to discuss openly and without fear of retribution issues of race as they relate to equity of opportunity and outcomes. And second, once that barrier is removed, Chattanoogans must transition from seeing loving kindness, or charity, as the sole means for changing lives. As Sarah Morgan of the Benwood Foundation says, “We have challenges in Hamilton County now that can’t be solved just with charity. It is time to focus on policies and systems that have perpetuated inequitable outcomes and results for students.”

The first step has proven difficult to take. “We’ve gone about as far as we can on systemic issues,” says Molly Blankenship, executive director of Chattanooga 2.0. “We can’t get any further until we address the cultural issues that are stopping us short of changing the trajectory of students in our schools.”

Chapter 3

“Talking about equity in Chattanooga has not been easy,”

says Blankenship. Representatives from partner organizations report that sometimes there’s a price to pay for speaking out against racism and for equity in Hamilton County, where some feel free to express racist ideologies or others place a premium on avoiding the discomfort that frank discussions of racial injustice creates. “It’s easier to prefer harmony over progress and change,” Blankenship says.

Bryan Johnson, Hamilton County Schools superintendent, says “equity” has become a term that some have loaded with meaning it shouldn’t have: “It’s necessary to understand the historical challenges that have existed. The historical challenges should not be threatening, but should provide necessary context as this critical work is underway. In some places and spaces, unnecessary divisiveness around the word ‘equity’ has been created because it became politicized. Educational equity is about children and closing opportunity gaps that have existed.”

Still, equity was a point of tension in 2020’s school board race. A debate between two school board candidates cohosted by Chattanooga 2.0 during the 2020 election season underscored ongoing tensions and disagreements.[11] One candidate said he supported equity as a priority and that some students need extra resources to succeed; the other candidate said he wished the word wouldn’t be used: “It’s a negative to a lot of people.”

Equity as “a negative to a lot of people” in Chattanooga informed how Chattanooga 2.0 positioned its early work; however, the partnership has become bolder and more forthright in calling out and addressing race-based inequities. The journey began in 2015 with the partnership’s release of an inaugural report that, as already noted, drew the connection between student outcomes and school zones that isolate students in schools by race. The report noted that “Hamilton County runs the risk of permanently creating two Chattanoogas—one for the prosperous and one for those being left significantly behind.” But it stopped short of saying those being left behind tend to be of color or that, as leaders of the Chattanooga 2.0 movement suggest, some quietly say there already are two Chattanoogas: “one for Black people and the one for white people.” The report aimed to be both a moral and economic call to action, with the economic call to action at the forefront of its title—“A Bold Vision for Our Future Workforce”—and in its notation that “the majority of Hamilton County residents do not have the level of education required by new local industries.”

That was 2015, when Chattanooga 2.0’s founding partners were getting a community to buy into an agenda. But as the partnership matured, it became emboldened and used its power as a convener to elevate equity as a core value. In response to concerns two school board members raised about proposals to advance equity-focused work in the school district in 2018, Chattanooga 2.0’s then-executive director, Jared Bigham, mobilized more than 130 community leaders to sign a letter in support of efforts to advance equity in Hamilton County Schools.[12] During the 2020 school board race, Chattanooga 2.0 hosted candidate debates with a local news station and the city’s newspaper that featured questions about equity, and it posted candidate responses to an equity questionnaire on its website.

Efforts to gradually chip away at the community’s reticence to discuss the connection between equity and race openly without concerns for retribution meant Chattanooga 2.0 and its founding partners would need to become bolder themselves. The murder of George Floyd in late spring 2020 was galvanizing for them, its weight crashing down on any remaining barrier to publicly calling racism “racism.” PEF’s senior leadership team issued a statement that it “is far past time to address…systemic racism.” The Benwood Foundation observed that racial disparities “hold a mirror up to the reality within Chattanooga,” where the growth and progress the community has experienced “does not lead to real opportunity for people with black and brown skin.”[13] And the Chattanooga Area Chamber of Commerce issued a statement committing to the “fight to eliminate racism,” recognizing that “while we have prioritized inclusion and diversity in our work for our community, this is not the same work it will take to eradicate systemic racism. Our ears are open, and our hearts and hands are ready for the work ahead.”[14]

Blankenship coordinated the writing of an op-ed with Chattanooga 2.0’s steering committee of partners, including PEF. It acknowledged “generations of systemic racism against Black and brown communities” and argued that the time had come for Chattanoogans to set aside their desire for harmony: “We must be brave enough to be uncomfortable…We must place a commitment to achieving true equality and justice at the center of our work.”[15]

“Chattanooga 2.0 was built on a commitment to advancing equity and school turnaround work that long predated our launch. And there are other equity efforts that are adjacent and complementary to the work the coalition does. What we did was pull together a broader set of stakeholders we feel are uniquely positioned to lead equity-focused work on the education to workforce continuum.”

Partners combined these watershed public statements with the creation of an explicit definition for equity, posting it on Chattanooga 2.0’s website, where they observe that the Hamilton County community must distinguish between the notions of equity and equality: “Equity recognizes that each individual will need unique supports to cross the same finish line,” that only “intentional supports, resources and policies designed to meet individual needs will eliminate disparities in outcomes.”[16] Superintendent Johnson says the distinction Chattanooga 2.0 made is no different than what he did when he coached student athletes to get them ready to compete: “When I coached football, my job was to develop tailored plans so that individual student athletes had every opportunity to be successful. If I had a lineman who wasn’t as quick as some of the other student athletes he was competing with, I might develop a specialized nutrition plan for him and coach him on his footwork. He simply needed something different than other student athletes so he could compete. Not all student athletes start from the same place.”

Blankenship reports that the partners are in the process of developing an equity plan for Hamilton County to help put the equity statement into action. It will, she says, reflect what backbone organizations do best: “focus on convening partners to align their priorities and build their capacity to develop and execute key equity strategies and drive change by strengthening the Chattanooga 2.0 coalition’s leadership role around equity.” The partners will be looking to address “upstream issues such as housing and health that affect education opportunity and outcomes,” she says. And they plan to convene an equity council that will prioritize strategies to advance an equity agenda for the county—“along with anti- racist practices.”

By 2020, the Chattanooga 2.0 partnership had done what it hadn’t in 2015: placed racism on the table and called out the need to develop practices designed to address it.

Chapter 4

Rebecca Ashford thinks higher education has a chance to get it right.

As president of Chattanooga State Community College, she believes colleges should stop worrying about whether students are “college ready” and focus instead on becoming “student ready,” noting that institutions of higher education have been complaining about the preparation of their students since they were founded in the 17th century in what became the United States. “It’s always someone else’s fault,” she says. “That’s why collective impact efforts are important. K-12, higher education and nonprofits should all be in this together.” Bryan Johnson, superintendent of Hamilton County Schools, agrees, observing that school districts are “so focused on finite periods of time that we can miss the broader purpose” and that it is “critical that we have an entity like Chattanooga 2.0 to connect the dots across systems so that students matriculate into postsecondary and eventually into careers.”

Ashford sits on the Chattanooga 2.0 steering committee and with her peers is committed to bringing change to her institution and increase its graduation and retention rates, especially for students of color. This, she knows, means that her institution must become more student centered—systemically.

Change—especially in large institutions such as community and four-year colleges—doesn’t happen overnight, however, and sometimes systems change work begins with programs funded by charities that stakeholders rally around.

The short-term play of the mentorship program is charitable, a foundation-funded intervention designed in some respects to do what the college-educated parents of middle-class children do for them: run interference through college bureaucracies they themselves worked through a generation before.

The long-term play for Chattanooga 2.0 and its partners is systemic, however. They know that historical inequities on one hand and immigration that presents opportunities for the children of newcomers on another will mean that students of color and the less affluent will need help deciphering the hieroglyphics of federal, state and private institutions well into the future even as more institutions become more student centered.

Chattanooga’s College Advancement Mentorship Program

With funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, PEF and its partners, including Chattanooga 2.0, initiated its College Advancement Mentorship (CAM) program in the fall of 2019. Each of ten mentors PEF hired supports approximately 100 students who are either rising college freshmen or first-year college students at Chattanooga State, UTC, Lane or other colleges across the region. Trained by PEF on how to help students complete college applications, apply for financial aid, identify and pursue services on campus or in the community and self-advocate, the mentors work with students from PEF’s targeted six high schools. Stacy Lightfoot, vice president of college and career success initiatives for PEF, says their job is to stop up leaks in the system that occur between high school graduation and the first day of college and during their first year, when many students leave.

Lightfoot notes that Magdalena Perez “was put in a situation in which far too many of our first- generation students of color find themselves, having to navigate a system that was not designed to support them. She was asked to uncover and solve problems that weren’t of her own making—problems that ultimately took two tries and the persistence of her CAM to work through.” Lightfoot notes that “Maggie won’t need that support anymore. She knows how to advocate for herself. That’s a lasting result of her work with her CAM.” She adds, “Her challenges uncovered structural problems at the college that were elevated to avoid similar circumstances occurring in the future.”

Ashford sees the college advancement mentors (CAMs) as system change agents who are having an impact on both institutional culture and practice. “I invite the CAMs to attend internal meetings so they can tell me and others the good, the bad and the ugly about Chattanooga State,” she says. She observes that the mentors “tell us what’s going on from a student’s point of view. They tell us what’s working and what’s not.” Their knowledge of the student experience is why Ashford plans to involve the mentors in the campus’ strategic planning process. Their insights, she believes, will help the institution become more student centered, welcoming and responsive to the needs of students of color.

Yancy Freeman, a vice chancellor at UTC, explains that as change agents, the mentors are teaching the university about gaps in service: “Those in the enrollment part of the house meet with CAMs on a regular basis and discuss where we might be falling short. We try to make changes based on what we’re learning.” In particular, he says, they demonstrate how important the work they do is to retaining students of color who are also experiencing poverty: “We couldn’t do this without them. The role they play in supporting students through their academics and their personal trials as first-generation college students on a campus where there aren’t a lot of students of color is pivotal. It’s hard to get to learning if you’re hungry or if something else is getting in the way of your focus.They are keeping students enrolled who might have otherwise found the experience just too much.”

Stacy Lightfoot, longtime Chattanooga resident and PEF’s vice president of college and career success initiatives, says the mentors demonstrate that the structural supports they provide are essential to students who have not had the same opportunities or social capital as white, middle-class students. “We have structures in place for college access,” she says. “High schools employ college advisors. But we also need permanent structures for the college mentors. The CAMs are helping campuses realize that.”

Early signs indicate the mentors have had an immediate impact on retention. Data collected by PEF show increased retention rates for students between fall and spring semesters in 2018-2019 and 2019-2020: six points for UTC and four points for Chattanooga State. Lightfoot observes that the differentiated supports PEF provides need to become institutionalized in the region’s higher education institutions: “The CAMs are helping students now, but more importantly we designed them to be catalysts for systemic change. The current mentees may get into and through college because of their work with mentors. That’s a really good thing. But we need to think about the kids who will follow.”

Lightfoot adds that PEF is banking on the fact that the strong relationships and structures they’re building together will result in lasting change. “We don’t want students like Maggie Perez to be the exception any longer. We want Maggie to be the rule.”

Chapter 5

A lot of the most important assets Chattanooga 2.0 has are intangible relationships and collaborative structures

that allow a backbone organization coordinating a collective impact initiative to step into places that others can’t and quarterback responses across organizations to issues,” Blankenship says of the partnership’s role in responding to the outbreak of COVID-19 and the school closures that ensued. “I’ve realized how important informal authority is. We’ve utilized collaborative infrastructure to bring people together in a time of real crisis.”

Before the pandemic, Chattanooga 2.0 exercised its informal authority as it convened and managed the county’s Children’s Cabinet.[17] Members of the cabinet include leaders of nonprofit organizations and county and city government staff. Blankenship facilitates their efforts to break down silos across organizations, ensure greater coherence and collaboration across agencies and institutionalize structures and processes that survive changes in leadership. The structure that existed when COVID-19 struck allowed Chattanooga 2.0 to coordinate emergency responses to school and wraparound program closures. In April 2020, Chattanooga 2.0 began convening weekly meetings of the cabinet and local policymakers, government agencies and system-level leaders. Blankenship orchestrated data-sharing agreements across organizations so that Chattanooga 2.0 could create and monitor a data dashboard, which included information on students who weren’t participating in virtual learning. The information allowed partners to locate and engage them. The group also fostered the expansion of virtual summer programs to support student academic enrichment and emotional development.

COVID-19 ignited a sense of urgency in the group that hadn’t existed before, extending it well beyond Chattanooga 2.0’s founding partners. “It exposed inequities and made them tangible for people,” Blankenship says. “It made things possible all of a sudden.” Seeing that many of Hamilton County’s children did not have the hardware or the internet access to participate in virtual learning made it clear to all, Blankenship says, that low-income students don’t have the means to participate in learning in the 21st century, let alone during a pandemic. To address the systemic inequity in the short term, Chattanooga 2.0 and partners raised $100,000 to pay for Chromebooks and worked with a municipal utility, EPB, to set up free Wi-Fi access points in public housing and other low- income communities.

For the long term, the team worked with EPB to create HCS (Hamilton County Schools) EdConnect, a program that lives within the school district and guarantees internet access for 27,500 low-income students and 17,000 households for 10 years. The city of Chattanooga, Hamilton County, the school district and corporate and foundation donors provided $8 million to cover up-front costs.

Reflecting on the community’s ability to address a key inequity in the county systemically, Blankenship says, “We saw a window open around expanding broadband and we did it. Taking on big issues like the digital divide requires a quarterback to get everyone organized around a common agenda that transcends those individual organizations. A backbone organization sitting at the nexus of sectors and systems can create bridges across organizations, making the impossible possible.”

A backbone organization sitting at the nexus of sectors and systems can create bridges across organizations, making the impossible possible.”

To Varner, the community’s response to COVID-19 shows that Chattanoogans can accomplish almost anything when they set their minds to it, rally partners, and execute an action plan. “Hamilton County has intelligent, visionary leadership, people who embrace diversity and say they want to see all kids succeed. Look at what we have accomplished in response to meeting basic needs during the pandemic. We need to apply the same sense of urgency, intelligence, and energy to minimizing the negative impact of poverty as we have done to help some schools thrive and extend those practices and policies to our lowest performing schools.”

Chapter 6

Chattanooga 2.0 partners are optimistic about the future but acknowledge that addressing structural inequities will be an arduous task if it remains difficult to speak them out loud.

A community cannot address inequities, partners say, unless there’s consistent agreement that they exist. Still, 2.0’s partners see there’s been a lot of progress in the hearts and minds of white Chattanoogans since the days of Jim Crow. “It’s not like it was in the days of segregation,” says Edna Varner of PEF. “White parents don’t mind anymore if their children are sitting next to Black students in school like they once did. They care that they are getting what people of privilege demand: rigorous curriculum with lots of options.”

Varner says that far too many Black and Latino kids don’t have access to the same rigor. “Sure, we as Black people now get to go places everyone else does. But our kids are stuck in the same place we were decades ago.”

Getting Chattanooga unstuck is what the Chattanooga 2.0 coalition is trying to do. That work requires the cradle-to-career partnership to address structural and cultural barriers to equity. “We’ve made some progress with both,” Blankenship says, “but we can’t push any further on the structural issues until we’ve made more progress on the cultural ones.”

Partners say that Chattanooga needs to get to the point where it doesn’t take an act of courage to speak out against inequity. Getting to that point will help the community make another important transition, Blankenship believes, from looking to solve problems through charity to addressing them through what she says is a commitment to liberation. Liberating people, she says, means those with privilege are channeling charitable impulses into conscious efforts to permanently remove existing barriers to success. As PEF’s Varner says, “What we’re often doing in Chattanooga makes us feel good without addressing the real problems. It’s like giving a homeless person 20 dollars. We feel really good for a few hours. But the person is still homeless. We need to get to the heart of what’s really wrong—and it’s not students and their families.”

As Rebecca Ashford, the president of Chattanooga State, suggests, institutions need to stop thinking that students don’t have what it takes; institutions need to be student ready.

Magdelena Perez is a young adult who has shown that students have what it takes. Because of her parent’s love, her own grit and determination, a little help she received along the way from a stranger and through the intentional efforts of the cradle-to-career initiative’s partner, PEF, she’ll be the first person in her family to complete college. But a lot more children of Chattanooga will make it, partners say, when there are intentionally designed systems in place that acknowledge supports shouldn’t be parceled out in the same increments to all kids.

Indeed, they believe, Chattanooga can become a place where its exceptional spirit of loving kindness merges with a conviction that does not need to be as hard as it has been, Blankenship says. “Not all people in Hamilton County are starting at the same place. Let’s embrace that fact, roll up our sleeves and get

to work.”

Superintendent Johnson believes that Chattanoogans are positioned well to roll those sleeves up: “I’m hopeful because of the nature of people in Chattanooga. We have a giving group of people here. It’s one of the most loving communities I’ve ever seen.

The spirit of love, cohesion, collaboration and the sense of team that exists in our community will help us get through the challenges we’ve faced simply talking about equity. Then we’ll be ready to do the work.”

“Compared to other communities that are engaged in intentional racial reconciliation work, Chattanooga puts itself at a competitive disadvantage to those that are far less resistant to talking about systemic inequities and therefore addressing them.”

“We haven’t created a good welcome for our growing Latinx population,” says Sarah Morgan of the Benwood Foundation, a 2.0 partner. Stacy Johnson, the executive director of La Paz Chattanooga, says that though the population of Latinos in the city’s schools has grown to 17 percent, they are often forgotten, noting that her organization has often stepped in to offer language support for students, their families and other organizations to ensure communications are accessible for the community. Howard High School, established for the children of freed slaves in 1865 and an all-Black school just a few years ago, is now majority Latino. “We have to become more intentional about how we’re ensuring that our newcomers have good learning experiences,” Morgan says. “We need to make it clear to them that they matter and ensure there’s a plan for a bright future. Right now, we’re doing one-off things to help them. We need to be more systemic.”

1 Chattanooga 2.0 executive committee members are: Chattanooga Area Chamber of Commerce, Public Education Foundation, University of Tennessee Chattanooga, Hamilton County Schools, United Way of Greater Chattanooga, Benwood Foundation, Community Foundation of Greater Chattanooga, Chattanooga State Community College, LaPaz, PEF, Read20, Urban League of Greater Chattanooga

2 Chattanooga high on giving list, Chattanooga Times Free Press, August 23, 2012. The newspaper used data provided by the Chronicle of Philanthropy.

3 Data provided by PEF and Chattanooga 2.0.

4 Information on Chattanooga’s history of court-ordered desegregation is taken from “From the hallways to the Courtroom: struggle for desegregation in Chattanooga, Tennessee 1954-1986, “Honors Theses”, Kelly R. Reed, UTC Scholar, University of Tennessee 2016.

5 See articles in Education Week and the Chattanooga Times Free Press for reporting on the merger. In 1941, Chattanoogans voted to charter a school district separate from the county. But white flight in the 1970s and a court ruling in favor of increased funding for rural schools drained city resources. Then, anti-tax sentiments of Chattanoogans concerned about paying both city and county school taxes climaxed in citizens voting for the city school district to be absorbed by the county.

6 See Twenty years after schools merged, new leader faces similar challenge, Chattanooga Times Free Press, August 10, 2017.

7 Ibid.

8 See Brown v. Board of Education 60 years later: What the desegregation case has meant for Chattanooga area schools, Chattanooga Times Free Press, May 17, 2014.

9 See A Bold Vision for Our Future Workforce, Chattanooga 2.0, 2015.

10 See A Bold Vision for Our Future Workforce, Chattanooga 2.0, 2015.

11 See a recording of the 2020 school board candidate debates here.

12 Text for the letter can be found here.

13 The statement was originally posted on the Benwood Foundation’s website and is no longer accessible. An archived version of the statement can be found here.

14 The Chattanooga Area Chamber of Commerce’s full statement can be found here.

15 See Blankenship: We must be brave enough to be uncomfortable, Chattanooga Times Free Press, June 7, 2020.

16 See Chattanooga 2.0’s website

17 To read more about the Children’s Cabinet and the By All Means Initiative, click here.