Buffalo Refuses To Lose

The We Refuse to Lose series explores what cradle-to-career initiatives across the country are doing to improve outcomes for students of color and those experiencing poverty. The series profiles five communities—Buffalo, Chattanooga, Dallas, the Rio Grande Valley and Tacoma—that are working to close racial gaps for students journeying from early education to careers. A majority of these students come from populations that have been historically oppressed and marginalized through poorly resourced schools; employment; housing and loan discrimination; police violence; a disproportionate criminal justice system; and harsh immigration policies.

Since early 2019, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has supported these five community partnerships and convened their leaders as a learning community. It commissioned Education First to write this series to share how these communities refuse to lose their children and youth to the effects of systemic racism and a new and formidable foe—COVID-19.

Chapter 1

A lot of people in the Black community don’t go to the doctor because they don’t trust them,

says Temara Cross, a 21-year-old graduate of Buffalo’s Hutchinson Central Technical High School. “That’s one of the reasons we have health disparities.” Now a college senior at SUNY Buffalo, where she takes graduate coursework in public health while completing undergraduate degrees in African American studies and pre-health, Cross says she “hasn’t been the same since” a school-based Say Yes Buffalo family support specialist introduced her to the organization her junior year in high school.

Five years later—after participating in several Say Yes programs—Cross has big plans for her future and the future of her community on Buffalo’s East Side. She is determined to increase her family’s and neighbors’ trust in doctors.

Cross plans to attend medical school, become a primary care physician and launch a health facility to mitigate health disparities that exist in her community. She says these disparities result from a complex set of historic inequities in education, transportation, housing and employment, among other factors. “But,” she adds, “I know from personal experience, from talking to people in my neighborhood and from my college studies, that they are in part due to a lack of trust in the medical profession.”

Cross says the lack of trust has its origins in history. As an example, she points to a clandestine medical experiment orchestrated by the U.S. Public Health Service between 1932 and 1972: a study to examine the progression of syphilis in men—without treatment. For the “Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment,” the government recruited 600 Black male Americans, nearly 400 of whom it diagnosed with syphilis. The Health Service never told the 400 men they had the disease but did tell local doctors not to treat them even when penicillin became widely available in 1945. The aim of the study was to research the progression of the disease until it finally killed the men, at which time, medical autopsies would be conducted to measure its ravages on the body.[1]

Once publicly disclosed in the 1970s, the experiment fueled higher levels of mistrust for doctors and lower levels of the pursuit of healthcare in the Black community.[2] Cross says her grandmother shared this lack of faith. As she was dying of heart failure with multiple comorbidities, Cross learned her grandmother stopped going to the doctor because she was tired of seeing medical professionals who didn’t look like her. This, Cross says, got her thinking about the root causes of health disparities.

Cross started asking questions of her neighbors. She heard them question the integrity of doctors and share worries about being injected with something that might be harmful. As recently as the summer of 2020, she says, hints of the arrival of a vaccine for COVID-19 led her mother to tell her she shouldn’t get vaccinated until “there’s proof that it works on Black people.” Distrust of vaccinations—not only for seasonal flu but also for eventual COVID-19 shots—is in fact widespread in the Black community nationally because of a history of forced vaccinations and medical experimentation within it.[3] And it is present in the young people of Buffalo. One hundred percent of Black high school students who participated in a summer 2020 Say Yes Buffalo focus group said they would not take a vaccination for COVID-19 when it becomes available.[4]

Cross, however, refuses to let her community lose to history. She plans to rebuild trust that has been lost. Say Yes Buffalo has given Cross the opportunity to put that refusal into action. “Say Yes Buffalo is literally my life,” Cross says. “Without the universal scholarship for all Buffalo graduates, I would not be in college. I would not have been blessed with the opportunities that shaped my personal and career goals. The internship program exposed me to the research realm of medicine and helped develop my time-management, communication and conflict-resolution skills. From the internship program to the mentoring program, I am truly thankful for Say Yes Buffalo. I don’t know where I would be without it.”

Say Yes Buffalo is the intermediary for a cradle-to-career education movement that aims to strengthen the Western New York economy It invests in the education of Buffalo’s future workforce through focused efforts to boost high school and postsecondary completion rates. Engaging school district, nonprofit, government, business and foundation partners, it provides a last-dollar scholarship to all of Buffalo’s public high school graduates and a comprehensive set of supports to ensure that students succeed on the pathway from PreK to the workforce. Supports include developmental screenings for early learners; social services and provisions for basic needs such as food security; mobile health and free legal clinics; extended Saturday and summer programs; FAFSA completion and mentorship programs for high school seniors and college freshmen; a college support network of case managers at Buffalo-based colleges and universities; paid internships for college students; and a program for young men and boys of color. More than 60 elected officials, business leaders, educators, parents, school district officials and community and faith leaders monitor and facilitate the progress of the partnership through participation in two governing bodies: a community leadership council and an operating committee.

*Temara Cross has been a Say Yes mentor, mentee, ambassador and two-time intern its internship program. She also serves on the scholarship board.

With the support of Say Yes Buffalo, Cross plans to help change the life trajectories of the residents in her community. By becoming a doctor, she’ll also change her own and her family’s economic trajectory, a primary goal of Say Yes Buffalo.

Chapter 2

Say Yes Buffalo’s decision to focus on economic opportunity responds to the city’s history of racial and economic segregation.

Say Yes Buffalo’s equity-centered broad public goal is that every student in the city completes high school and earns a postsecondary credential. Its mission is to strengthen the Western New York economy by investing in the education of Buffalo’s future workforce. That’s why executive director Dave Rust says the end-goal of the partnership’s effort to advance equity is to ensure Buffalo’s students land living-wage jobs as adults.

Today, the city’s residents of color do not have equitable access to living-wage jobs—or enjoy an equitable share of the life outcomes many white families experience. Buffalo’s history—and America’s history—of racial segregation explains how this came to be. As Rust notes, Buffalo’s racial segregation and economic segregation are equivalents. “They match,” he says.

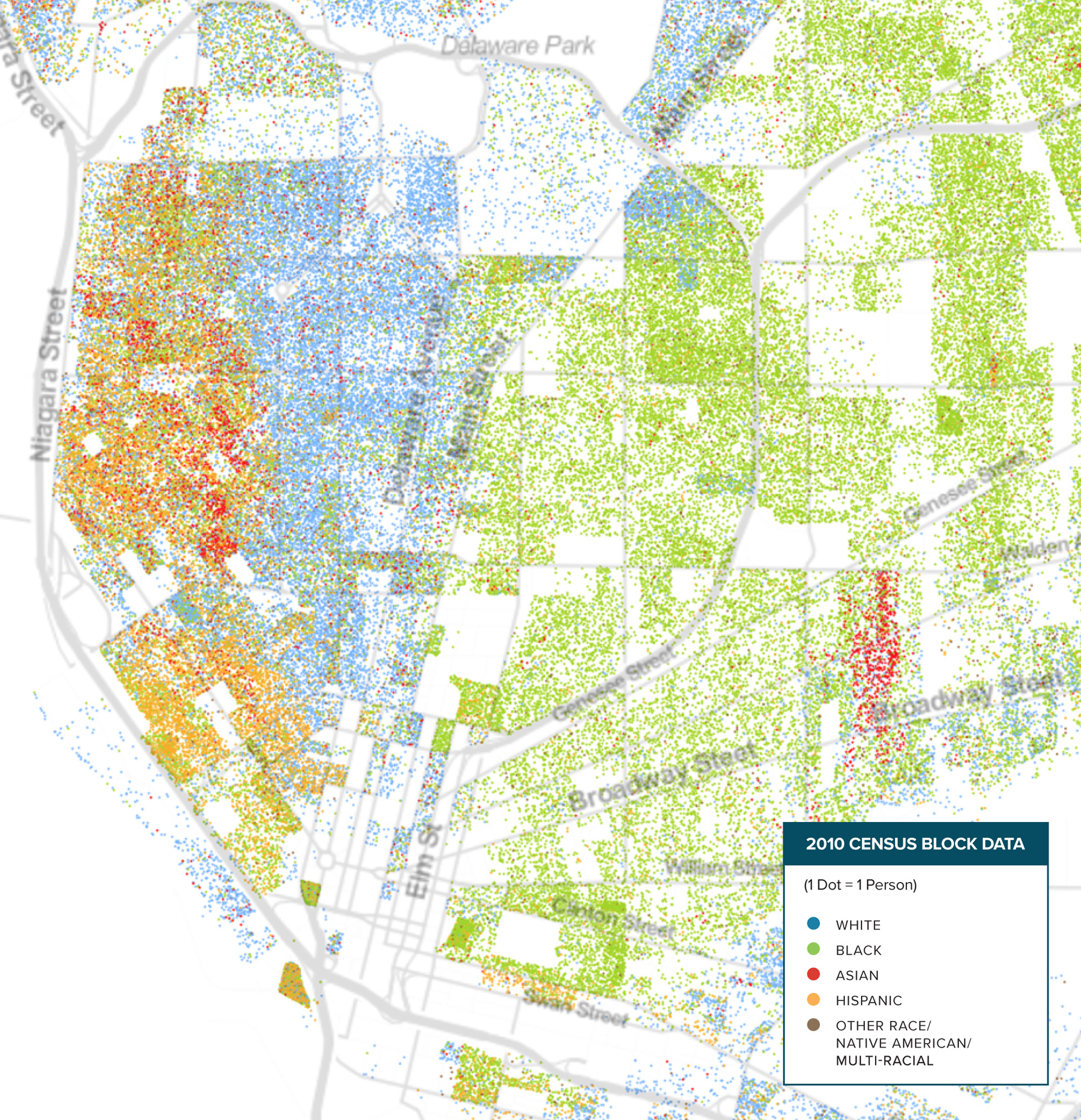

Seeded by workers and their families who came for manufacturing jobs, Buffalo’s population peaked in 1950 at 580,000. Then, Black residents accounted for less than five percent of the population. Between 1940 and 1970, their ranks increased by 433 percent, while the overall population went into steep decline as jobs shifted to other sectors or moved outside the city. By 2000, Buffalo had only 300,000 residents; the white population shrank to 50 percent (it was 97 percent in 1950), while the Black population grew to nearly 40 percent, isolated on the city’s east side.White flight and racist housing policies enacted in the 20th century drove the substantial change in the demographics of the city and the racial isolation of its residents. In the 1950s, federal and state governments subsidized white migration to the suburbs, paying for highway, water and sewer systems to make the exodus possible. Business and education facilities followed, taking jobs with them. Today, only one of the five major employment centers in Erie County is in the city of Buffalo.Main Street has always been the stark dividing line between whites and the city’s East-side Black population. Restrictive covenants made it impossible for people of color to assume the deed of a home on the other side of Main Street. Redlining, a federally sanctioned discriminatory lending practice that denied home loans to people of color and restricted investments in their communities, resulted in urban blight and made it impossible for Black families to build wealth through homeownership. As federally funded public housing emerged in Buffalo in the 1950s and 60s, the “prevailing composition rule” dictated that occupants of individual public housing projects be of the same race. As white communities rejected these complexes, public housing in the city became nearly all Black and all East Side.Today, 85 percent of Black Buffalonians live east of Main Street even though Buffalo’s population is closely divided between white (45 percent) and Black (37 percent) residents.

Source: A City Divided: A Brief History of Segregation in Buffalo, Partnership for the Public Good, 2018

The root causes of racial and economic segregation in Buffalo are little different from those in most northern American cities, especially those in the Rust Belt—though Buffalo-Niagara, as the nation’s sixth most segregated metropolitan region, is among the most extreme [5]. They include racist housing and lending practices that isolated people of color on the east side of the city and created urban blight, state-subsidized white flight and employment discrimination, among other factors (see sidebar above for a history of segregation in Buffalo). [6]

Today, racial segregation plays an outsize role in access to quality employment, schools and food, and to clean air, water and soil, reports Buffalo’s think tank, the Partnership for the Public Good. Whites living west of Main Street—the city’s racial dividing line—live five years longer than Blacks residing east of it. On the east side of the street, hospital admissions are three times higher, there are more toxins in the soil, homes are tucked against highways and residents have increased incidences of respiratory illnesses [7]. In 2015, white households in the region had an average median income of over $56,000, $3,000 above the national average. Black and Latino median incomes were less than half that at $25,652 and $27,209 respectively. These income levels reflect job opportunities and employment rates that are not distributed equitably. White workers in Buffalo are most likely to be employed in high-opportunity jobs, Blacks the least likely. 2018 unemployment rates for Blacks and Latinos were double that of whites [8].

The data underscore why Say Yes Buffalo’s emphasis is on providing greater economic opportunity for the city’s students of color. To bring opportunity to all Buffalo’s residents, the city needed to come to grips with its education outcomes and realize it needed a lot more hands on deck to improve outcomes. Community leaders determined in 2011 that they would create a cradle-to-career education partnership as a result.

“What Say Yes did was put together this powerful north star of a universal scholarship for all graduates to a SUNY school and access to 100-plus colleges across the nation. That north star shifts attitudes and outcomes. That is the pull. The push is a system of comprehensive supports focused on removing barriers and providing social emotional learning supports.”

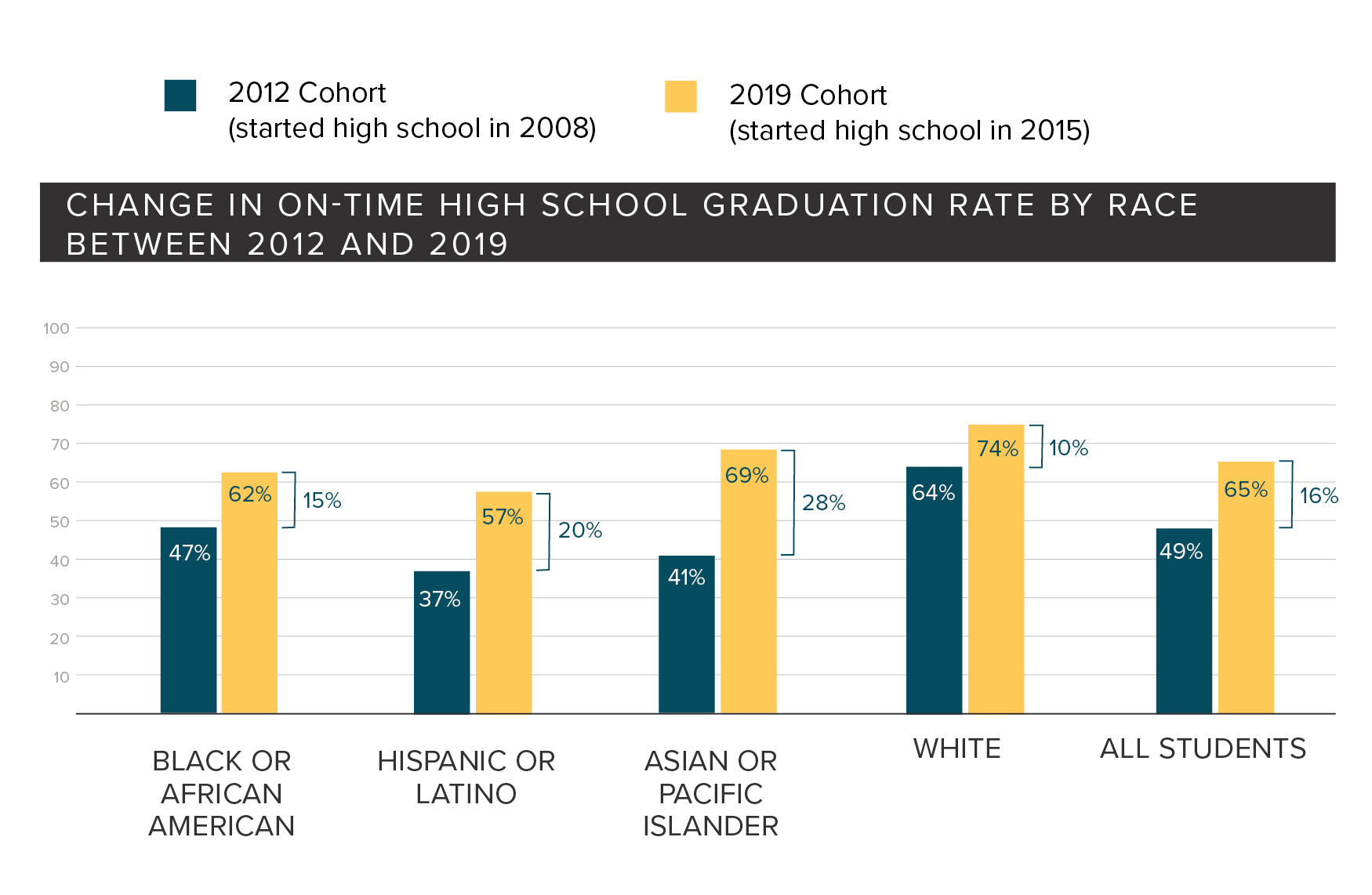

Say Yes Buffalo “emerged out of tragedy,” says Rust, referring to 2012’s 49 percent graduation rate for a city school district that is 20 percent Latino, nine percent Asian and nearly 50 percent Black. “That’s unacceptable.”

Rust adds, however, that “the solution is more important than the problems.”

That solution-orientation led the founders of Say Yes Buffalo to address a root cause of low high school graduation and matriculation rates for students of color: the income inequality at the heart of race-based economic segregation. As a result, the cornerstone of Say Yes Buffalo’s efforts became its scholarship program to make college affordable—backed by numerous student-centered supports to address other barriers as students navigate the path to college and career (Say Yes to Education—a national organization that fostered the creation of local Say Yes to Education chapters across the United States—provided $15 million and technical support to help Buffalo launch and implement its programs).

In less than a decade, Say Yes Buffalo has raised nearly $70 million for postsecondary tuition scholarships toward its goal of $130 million. This goal includes a $100 million endowment to fund universal last-dollar tuition scholarships to attend any New York State public college or university and over 100 private institutions. There are currently 2,500 active scholarship recipients.

Clotilde Perez-Bode Dedecker, president and CEO of the Community Foundation for Greater Buffalo, which led the effort to launch Say Yes Buffalo, says the universal scholarship is an incentive that has shifted attitudes and outcomes: “You have to be able to see the basket if you are going to shoot and score. When families can see the basket, they know postsecondary education is possible. They engage more because they know there is a real possibility for their kids to succeed.”

Tommy McClam, who directs Say Yes Buffalo’s Breaking Barriers initiative, part of the My Brother’s Keeper National Alliance, says that the organization’s commitment to preventive services is part and parcel to the My Brother’s Keeper ethic that informs all of Say Yes Buffalo’s work. “That’s what cradle-to-career initiatives are all about,” he says. “It’s about taking care of our brothers and sisters. You’re making sure kids are taken care of from birth until they eventually earn a living wage. If a kid isn’t doing his schoolwork because she’s hungry, you feed her. If the gas isn’t turned on in her home and she’s cold, you go to the utility company and turn it on. If there’s a shortage of baby formula, you know that’s going to affect an infant when she’s in kindergarten, so you find a way to get the parents the baby formula.”

The supports that complement the scholarship program stretch from children’s earliest years through their postsecondary and employment experiences. They combine to remove the financial, academic, social and health-related barriers to college access and completion. Many supports are offered directly by Say Yes Buffalo staff embedded in the city’s schools and are a mix of education supports and preventive services (see sidebar on page 3 for a list of specific supports).

Two programs in particular facilitate the transition from high school to college and college to workforce.

For its mentoring program, staff recruit volunteer mentors who are often from the corporate sector. After receiving intensive training, mentors commit to making four virtual and/or in-person contacts per month for 18 months—from their mentee’s second semester senior year in high school through the end of the freshman year in college.

Through the 2019–20 school year, a total of 141 students worked with Say Yes Buffalo mentors; 95 percent matriculated to college, and 80 percent persisted through their first year and entered their second, compared to 62 and 69 percent respectively for all Say Yes Buffalo scholarship recipients.

The internship program for college students provides a resource many affluent and connected families enjoy. “We provide the social capital that the parents of our scholars do not have,” Rust says. “Others can call up banks or corporations and get their sons and daughters into internships. The bulk of our parents work two to three jobs but don’t have the social access to these employers. We do. So, we make those connections.”

One of the two staff members Say Yes Buffalo dedicates to the effort makes the connections. The staffer works directly with employers, securing a bank of internships related to the career pathways of scholars and communicating time and financial commitments, including paying interns a minimum hourly rate of $11.50. The other staffer works with the interns, orchestrating a succession of training sessions to ensure they succeed on the job and keeping tabs on them while they’re working.

In the 2018–19 school year, Say Yes Buffalo placed 86 student interns. The social capital deployed by Say Yes Buffalo pays off for these students. In the case of Temara Cross, it resulted in skills she’ll need to be a successful doctor. For others, it pays off in jobs. Rust reports that each year, some of the interns receive job offers from employers they interned for. Of the 86 interns, 12 have been offered full-time employment.

The scholarship program and comprehensive supports provided by Say Yes Buffalo and its partners contributed to the city’s increased high school graduation rate between 2012 and 2019 (see table below) and an eight-point increase in the college matriculation rate, from 57 to 65.

Rust says that Say Yes Buffalo and its partners have a lot of work to do to graduate still more students but calls these results a “big step forward from where we were seven years ago.”

To push forward further, Say Yes Buffalo is building social capital that does not currently exist for many of the youth it serves. The partnership also helps them establish mindsets for themselves that success in school and life is their destiny, not a dream that the culture of white supremacy can defer any longer.

Chapter 3

Say Yes Buffalo is helping young men and boys of color create more positive and accurate narratives of themselves, paving the way for their success in school and life.

Tommy McClam manages Say Yes Buffalo’s Boys and Young Men of Color initiative (BMOC), one of ten projects of the Greater Buffalo Racial Equity Roundtable, an effort anchored at the Community Foundation for Greater Buffalo. In 2016, the Roundtable decided that Say Yes Buffalo was the organization best situated to create and host the program.

The Roundtable’s goal is to achieve an expanded, inclusive economy in the region, says Felicia Beard, who administers the Roundtable’s work for the foundation. “There is a moral case for racial equity,” she says. “We also make the economic one. When everyone can make a living wage, we all win.”

Tommy McClam’s Narrative: A Family That Refused To Lose

Tommy McClam understands at a deeply personal level why the narrative change work Say Yes Buffalo’s Breaking Barriers program does with young men and boys of color is important. He brings his own story of narrative transformation to the table. It is the story of an American family, though it is far more transcendent than most and colored by love despite the privations and horror his ancestors endured. McClam is three generations removed from slavery. On a journey to the South to trace his family’s roots, he studied preserved slave ship logs in Charleston, South Carolina, once America’s largest slave-trading port. In one, he found his great grandfather listed as “chattel,” along with chickens and a rake. In another record, he learned that at 16, on the Charleston auction block, his great grandfather was sold into slavery to a plantation that bore the name McClam.

McClam’s grandfather was a sharecropper in South Carolina following the Civil War and never attended school. As the son of a sharecropper, McClam’s father had little time for school and stopped attending at 14—after completing the 4th grade. McClam recounts how two years later, his dad forged his enlistment papers so he could join the military because he knew if he stayed in South Carolina, “he would wind up dead.” His sister, McClam adds, “came up missing, and everyone knew it was the Klan that grabbed her, and he could be next.” After serving his country, McClam’s father moved to Buffalo and worked for 30 years at Bethlehem Steel. McClam’s aunt was never found.

“My father asked me every morning if I loved myself,” McClam says. “He taught me that if I didn’t love myself, I couldn’t love others. He also taught me the importance of understanding my identity and purpose.” That’s easier said than done, McClam observes: “I still carry a piece of slavery with me every day: a slave owner’s last name. I can’t get rid of that. Think about that challenge: carrying that name but still trying to find your identity. That’s why the narrative change work at Breaking Barriers is so important. The youth that we serve need the same sense of purpose, the same love of self that my father taught me to have.”

Ensuring that everyone wins means that everyone knows they are destined for success. Many young men and boys of color, however, have not developed stories about themselves that self-suggest winning outcomes for their lives, McClam observes, adding that he knows “from personal experience how important having a positive view of oneself is.”

Michael Walizada, a 23-year-old alumnus of BMOC’s Breaking Barriers program, understands the impact that it has on participants. He says their mindsets have been shaped by false narratives. “Positive stories of young men of color are not sufficiently told,” he says. “They’re overshadowed by stories of challenge, stories outside the standard deviation of the real stories of boys and men of color.”

He explains where this left him at the start of his engagement with BMOC: “As a result of these stories, I internalized negative false perceptions that had an impact on my self-esteem, self-confidence, my outlook on the future and my career. Before my brothers start the program, they’re dealing with the same issues. They have to overcome barriers that other groups may not have, barriers that I have had to overcome.” Rashid Shabazz, a national leader in narrative change work for boys and men of color who has helped McClam shape Say Yes Buffalo’s Breaking Barriers effort, affirms Walizada’s perspective. “We want the young men and boys to understand the way culture is telling the story about them and how it impacts them negatively and positively, how white supremacy continues to reinforce stereotypes and barriers that have harmed and disadvantaged young men of color,” Shabazz says. To counter this negative influence, he continues, “We also want them to become storytellers of their own experience, not as problems to be fixed but as assets, as the solutions to the challenges that affect them most.”

“[Breaking Barriers] bombards the youth with middle-class messages. They hear men of color talking about how to get a job and be successful in it. They hear about buying a house. The boys and young men are in a network of people who will help them.”

Breaking Barriers’ young men and boys gather two times a month for a year, graduating and earning a jacket if they meet program goals. Near the end of the first year, they must find another young man in their community who needs what they received and become a peer mentor to him for 12 months, as they complete the second year of the program. The first cohort of 40 young men and boys ages 12–24 convened in 2017. Amidst the pandemic in spring 2020, a third cohort finished a year of intensive work focused on identity, purpose and story-telling, reinforced by community service and advocacy, where the youth demonstrated for themselves they have both purpose and agency.

McClam points out that the narrative change work is not a one-off, two-hour session; it informs all discussions the youth have—and all the service and advocacy work they do. The young men and boys carry the sense of purpose and agency into the work that they do in school and their communities. “The intent is that they’ll carry this sense of identity and purpose throughout their lives,” says McClam.

The narrative change work takes place within the context of a national network—the My Brother’s Keeper Alliance. The “brother’s keeper” concept grows out of the Judeo-Christian tradition that asks people to do what Cain failed to do for Abel: look after him and keep him well. The Breaking Barriers’ “Creed,” composed by the youth themselves and spoken at the start and completion of every meeting, ends with a question followed immediately by its answer: “My brothers, I ask you, who are you? I Am My Brother’s Keeper.” [11]

For McClam and participants, implicit in this language is the notion that each cohort of graduates establishes a legacy—or social capital—for their brothers who follow them. Walizada is taking his role as a legacy-maker to heart as he enters Buffalo’s workforce with a newly minted master’s degree in business administration. He’ll be working in the accounting department for the National Hockey League’s Buffalo Sabres.

Christopher St. Vil, an assistant professor at the University of Buffalo who has evaluated the program, observes that the Breaking Barriers curriculum includes numerous interactions with men of color from multiple generations. “They bombard the youth with middle-class messages. They hear men of color talking about how to get a job and be successful in it; they hear about buying a house,” he says. Likening this exposure to Ivy League networks that perpetuate the privilege of elites in the United States, he adds, “The boys and young men are in a network of people who will help them.”

The ethic of “helping others” that informs the work of Say Yes Buffalo is present in its Breaking Barriers program. That ethic would position the organization to respond to the unexpected, a pandemic that would exacerbate inequities in the city’s communities of color, placing their health, well-being and successful educational outcomes at risk.

Chapter 4

Say Yes Buffalo has been well positioned to respond to COVID-19 and help students stay on track for postsecondary success.

Say Yes Buffalo fulfills multiple needs, providing money for postsecondary education along with education supports such as mentoring and extended-day programs. It also doesn’t shy away from the fact that children who don’t have their basic needs met aren’t likely to graduate from high school, let alone college. So Say Yes Buffalo and its partners do what they can to meet those needs.

In the best of times, Say Yes Buffalo works to make sure the basic needs of the city’s students and families are met. In the worst of times, with unemployment soaring and schools closed because of a global health crisis, it’s all hands on deck.

In a nod to the vital role Say Yes Buffalo plays in its community, Erie County gave the organization a portion of its federal Coronavirus relief funds to operate 48 virtual learning centers in partnership with the school district. The centers are serving up approximately 2500 students in grades K-8, acting as lifelines for the city’s students and working parents.

Since spring 2020, Say Yes Buffalo has partnered with several organizations to provide food and care packages that include clothing, masks and hand sanitizer to families. In spring 2020 alone, Say Yes family support specialists, deemed “essential workers” by the state of New York, coordinated 1,325 home visits with Buffalo Public Schools students and families, linking nearly 900 of them to organizations that meet basic needs.

At the same time, Say Yes Buffalo had its existing and soon-to-be scholars to keep on-track for postsecondary matriculation and college completion.

From March to June 2020, mentors made more than 4,000 virtual contacts with mentees. Say Yes Buffalo orchestrated a two-week virtual college tour series featuring 19 colleges and universities, provided virtual support for Say Yes Buffalo scholarship and financial aid applications, held a college-kickoff meeting for 125 students in collaboration with BPS, and conducted outreach to connect scholars to basic services and other supports. In response to needs uncovered on these calls, Say Yes Buffalo raised nearly $100,000 and worked with a local nonprofit to distribute 350 refurbished laptops and portable hotspots to scholars who did not have hardware or Wi-Fi to support virtual learning.

Michelle Sawyers, who manages Say Yes Buffalo’s College Support Network effort at Medaille College, notes how the pandemic has underscored the inadequacy of the term “digital divide”: “It’s a chasm, not a divide.” According to Sawyers, some Medaille students (who had previously used campus computers) were typing papers on their smartphones. When shelter-in-place orders shuttered their places of work, they lost their jobs and could not pay for their cell service.

Nearly 50 Say Yes Buffalo’s scholars enrolled at Medaille received computers and/or hotspots, Sawyers reports. As McClam says, “It’s part and parcel to what Say Yes Buffalo does.”

Chapter 5

Say Yes Buffalo’s staff, board members and partners believe that more must be done to help Buffalo residents understand and act on the city’s history of racial and economic segregation.

They are optimistic for how Buffalo’s story will unfold as it addresses historic inequities in the city—in part because its past also includes more charitable instincts than those that led to the city’s profound racial and economic segregation. Community Foundation for Greater Buffalo’s president and CEO, Clotilde Perez-Bode Dedecker, notes that Buffalo “is just a stone’s throw from Seneca Falls,” the birthplace of the women’s rights movement, and was part of the Underground Railroad and a national leader in the movement to abolish slavery.

The city’s history of racial segregation makes it difficult, however, to undo the legacy of the past. While optimistic, Perez-Bode Dedecker notes how racial segregation has undone a central building block of community—it’s difficult to develop the willingness to take care of your neighbors if you don’t know them. An analysis of segregation in the Buffalo-Niagara region found the white isolation index to be nearly 90 percent, which means “there is a 90 percent probability that a white person will not have an interaction with a person of color.” 12

Knowing these stories, Beard says, is important to economic opportunity: “When was the last time you thought about minimum wage and the impact that has on life?” She observes that Say Yes Buffalo and its partners are having conversations “that ask employers to open their eyes and think, ‘Oh, my goodness, I have people working for me who have two jobs. What am I doing so that they have to work here and somewhere else? I must not be paying them a sustainable wage.’”

Perez-Bode Dedecker suggests that people in positions of power need to open their eyes to much more, noting that some bankers and CEOs in Buffalo don’t know the history of redlining and the impact it has had on people of color because “our education system has never taught it to them.” This is why she says it is important to “make people aware of how we have gotten to where we are,” observing that there needs to be much greater understanding about how the oppression of the past has produced the inequities seen in Buffalo today.

Listening to the stories of people who come from oppressed communities is key to taking action that advances opportunity, Perez-Bode Dedecker suggests: “In any system, everyone only knows the part of the elephant they touch. No one sees the whole animal. Meaningful engagement of residents is critical. We would not have gotten school-based mental health clinics if we didn’t have parents telling us they can’t get to the clinics outside their neighborhoods. We have to make sure people with lived experience are at the table.”

With the place he’s taken at the table, Michael Walizada, the alumnus from Breaking Barriers, wants people outside of his core group of brothers to touch the entire elephant. In a time when many are still advancing a narrative of people of color that oppresses them, he expects greater empathy and positive actions that support people who have been oppressed historically. “Underneath divisive political rhetoric and demagoguery, people of color are real human beings,” he says. “They have the same hopes and dreams as everyone else for themselves and their families. To understand a human being, you have to look past preconceived notions. You have to connect to them on a genuine human level.”

Say Yes Buffalo has been connecting to students and their families at that genuine human level across the cradle-to-career continuum for the past eight years. The organization and its partners are meeting students’ basic human needs, removing social- and health-related barriers to success, providing money their families don’t have so they can go to college, coordinating mentorships and internships and building their social capital.

Say Yes Buffalo and its partners are helping Buffalo’s children and youth speak the Breaking Barriers’ My Brother’s Keeper “Creed” into existence for themselves; they strive to give them the capacity to create and control their destinies so they secure living-wage jobs, live happy fulfilled lives and bring an end to Buffalo’s race-based economic segregation.

The “Creed” is key to what Say Yes Buffalo and its partners are trying to accomplish, McClam says. Together, they are speaking a creed into existence for the entire Buffalo community:

“We stand in solidarity with each other. We are each other’s keepers.”

1 See A Generation of Bad Blood in The Atlantic, June 17, 2016, and the CDC’s The Tuskegee Timeline, accessed September 14, 2020.

2 A Generation of Bad Blood presents research suggesting that this medical atrocity resulted in poorer health outcomes for Black Americans and “accelerated the erosion of trust in doctors and dampened health-seeking behavior and health-care utilization for black men.” See also the Washington Post’s Black doctors want to vet vaccine process, worried about mistrust from years of medical racism, September 26, 2020.

3 See the Washington Post’s Black doctors want to vet vaccine process, worried about mistrust from years of medical racism, September 26, 2020.

4 Data provided by Say Yes Buffalo, September, 2020.

5 Working Toward Equality, Updated: Race, Employment, and Public Transportation in Erie County, Partnership for the Public Good, July 2017.

6 See A City Divided, A Brief History of Segregation in Buffalo, Ann Blatto, Partnership for the Public Good, May 2018. Partnership for the Public Good is a community-based think tank that provides research and advocacy support to its partners, which include the Community Foundation for Greater Buffalo and Say Yes Buffalo.

7 Ibid.

8 Information on income, job opportunities and unemployment come from A City Divided, A Brief History of Segregation in Buffalo, Ann Blatto, Partnership for the Public Good, May 2018; Racial Disparities in Buffalo-Niagara: Housing, Income, and Employment, Robert Johnson and Clint McManus, Partnership for the Public Good, May 2018 (the brief cites data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2011–2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimate) and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, cited in Advancing Health, Equity and Inclusive Growth in Buffalo, Policy Link and PERE, 2017.

9 See Say Yes Buffalo Report to the Community, 2018-19.

10 Data compiled by Say Yes Buffalo, 2020.

11 To read the entire creed, click here. It speaks to the boys’ and young men’s respect for self, family and country, their commitment to creating and controlling their destinies, their being made in the image of God, their passion for community and their will to live and not die—among other professions of identity and purpose.

12 See Racial Disparities in Buffalo-Niagara: Housing, Income and Employment, Robert Johnson and Clint McManus, Partnership for the Public Good, May 2018.